Readers of this site will know of my evangelism for Josh Wilker’s website, Cardboard Gods. That appreciation redoubled when I read his book, Cardboard Gods: An All-American Tale Told Through Baseball Cards, which I couldn’t recommend more highly to you all. It is at once entertaining and deeply affecting – kind of magical, really.

Wilker’s book tour reaches Southern California on Thursday with his 7 p.m. appearance at the South Pasadena Library, co-hosted by the Baseball Reliquary. (This takes place in conjunction with the Reliquary’s exhibit, “Son of Cardboard Fetish.”) This seemed like a perfect time to talk with Wilker about a few of the many things that make his writing so compelling:

A big part of Cardboard Gods that migrated from the site to the book is the importance of what you think a player’s pose or expression on the card is telling you. Obviously, these are guesses on your part, but do you think the photos on the cards are nevertheless windows to the gods’ souls – a veritable truth you wouldn’t necessarily get any other way? Or are they more just windows to our own souls?

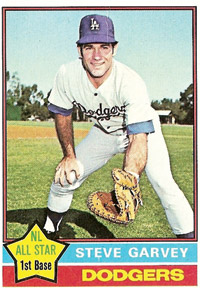

Lookin’ sharp, Steve

I don’t know if they get me to any truths, but they definitely have always been able to get me to start wondering. The moments captured in my cards from the ’70s would seem to most people to be flat and trivial, the kind of thing that no one, not the player, not the photographer, not the great majority of people who would ever look at the card, could ever care much about. But because I cared about them as a kid, the stiff poses and enigmatic expressions continue to have a hold on me now, especially because many of them seem to include the same element of aimlessness and absurdity that has threaded through my post-childhood years. So they exist in two worlds for me, the adult world and the child world, and so it’s no wonder I’m drawn to them, since I’m an adult who has been kind of perpetually haunted and fascinated by his own childhood.

Aimlessness is an important theme in the book, especially after your brother put up boundaries between the two of you as he got older. But one thing about your family is that it seemed passionate about intellectual pursuits – your dad, your mom, Tom, even Ian with all the reading he seemingly did. And even in your aimless days, you were thoughtful and imaginative to say the least. How come that didn’t translate for you into more interest or dedication to schoolwork as a kid? Was life just too painful to allow you to focus on school, to allow that to be an outlet?

For a while, I actually was very interested in school as a young kid, during the early years of the “free school” days. I think I mention in the book that there were times when I ran to school. Then puberty hit.

All of the teachers who came and went during the years I was in that multi-age, hippie-influenced class were great, but one in particular was very encouraging to me in terms of trying creative things, especially all kinds of ways to experiment with storytelling. I’d have mentioned her by name in the book but her name sounds like something I’d make up in a lazy stab at symbolism—Ms. Hope—but I do thank her in the acknowledgments under her given name, which she now uses, Dana Wentworth. I thank a lot of my teachers in the acknowledgments, but besides Ms. Hope they are all from my college and graduate school years, which is when I got passionate about learning again. I don’t know what was going on in all those in-between years when I was a terrible student. I just wasn’t interested, and I was definitely not getting much encouragement. It might have had something to do with pain, as you suggest. I mean, I certainly seized with gusto on the pain-killing properties of getting high as soon as booze and drugs came into my orbit.

Jack Kerouac

Was Kerouac in a sense the teacher that brought you out of it?

I like that question. He definitely helped, though I think to get at what was actually going on I have to talk for a second about the notion that I was in something that I needed to be brought out of. That’s very close to the way I would describe the situation myself, looking back at that span of months after I was expelled from boarding school, and it must have been the way most people would have sized things up, but I was more than merely aimless and lost. I was also high a lot, and not merely on substances, though that was a big part of it. I mean there were times when I felt like I was flying. Fragile as it was, I did sometimes feel a fleeting connection to ecstatic moments. Reading On the Road at that time in my life, it was the perfect thing, because it suggested that such a connection could be sustained, or at least could be the center of a story of a life. That book was one of three books that had a huge effect on me during those first beyond-school months of my life. The others were Frank Conroy’s memoir Stop Time and The Catcher in the Rye, which I’d read once before but which hit me a lot deeper this time. All three books held out the promise that I might be able to write about my life, but certainly On the Road spoke most forcefully to the idea that there still might be some joy in the world, and that the feeling of being high was not only an illusion.

How did the reborn thrill of reading those books translate into you becoming a writer? At the genuine risk of getting too fancy with this metaphor, but did writing then become a new drug or your methadone program? Was it an escape or a way to face reality? Or are those not mutually exclusive?

I certainly wanted to write something like the books I fell in love with that period of my life. After drifting around out of any kind of school for a few months, I went to a state college in Vermont, Johnson State, for two reasons: it was really cheap for a resident, and it had a creative writing major. In the book, I take a cheap shot at my degree (a BFA in creative writing) for the sake of a punch line and also to communicate how ill-prepared I was at the end of college to join the working world, but the truth is I had a couple of writing teachers at Johnson State, Tony Whedon and Neil Shepard, who got me started on my path in life. I’m very grateful to them for that.

There was definitely not a clear border marking the end of my “partying” and the beginning of my writing life. Really, I’d already been writing for years, in journals mostly, but even then with the idea that I was imitating my favorite narrators. The first time in college I got singled out for my writing was when Tony praised a creative essay I’d written and asked that I read it aloud. I had gotten high before class, so high it was sort of difficult to read my own writing.

Eventually, I eased off the pot because I found it difficult to focus while trying to write. But I still drank and drink to this day, and have been known to go to Amsterdam once in a while, too. As for whether writing became something with addictive qualities, I definitely wrote and continue to write with some level of compulsiveness, searching for a high, and also searching to escape reality, rather than to embrace it. This approach can lead to an empty, gnawing, dissatisfied feeling. It actually used to lead to me periodically ripping my notebook in half. Now I try to just see what’s in my mind and go from there, but I still am not evolved enough to not feel like crap if my writing is either not coming out at all or is coming out badly.

One more question on this path before I get to some of the book itself. I had it drilled into me at a young age – lovingly, but emphatically – that school not only mattered, but it was just shy of life and death. Now in my 40s, I’ve found plenty of proof among the people I’ve worked with that excelling at school is one path to success, but far from the only one – and it certainly doesn’t guarantee success. How much do you think it matters? And does anything matter more than the mentors you find to guide you?

I don’t know if I can offer much insight in what does or doesn’t guarantee success. I’d say I excelled in school as a little kid, in that I enjoyed it a lot was and creative and interested, then I was the picture of mediocrity and invisibility in my teen years, when my creativity and interest went AWOL, and then in college, as the pot haze lifted, I started excelling again, which then segued into years and years of sporadic, low-paying, mostly menial employment punctuated by brief glimmers or mirages of a suggestion that I was not wasting my life by focusing on trying to be a writer. Somewhere in the middle of this adult life, I got a master’s degree in a graduate writing program that I loved and am still drawing strength from but which put me into substantial debt that took many years to dig out of, what with my continuing efforts as a low-paid employee.

If I looked at my life from a macrosociological, class-conscious level, I’d probably conclude that my lousy high school performance squandered the cultural capital of my well-educated middle-class parents: if I’d been acing classes all along I could have gone from success (instead of expulsion) at the somewhat prestigious prep school my parents sent me to (by taking out huge loans that took many years to repay) to success at some revered University and from there to some kind of upper-middle-class-confirming “career.” It’s virtually taboo in America to talk about things in these terms, but excelling in school (or, in the case of those already established by familial standing in the ruling class, such as GW Bush, simply showing up at “the right” school) is the single most important means of maintaining or increasing the level of one’s social class. So in that sense, I guess I blew it by spending 10th-grade English class thinking exclusively about the boobs of the girl one row over, but that’s who I was and I couldn’t have been anyone any different, and I wouldn’t want to change things anyway. As I mentioned before, my crooked path led me to (among many other things) a couple of great teachers in college, and they sent me on my way determined to embrace writing as a lifelong practice.

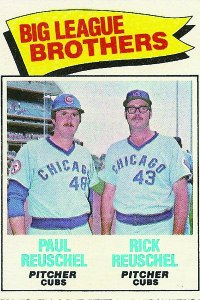

The Reuschel brothers, in no particular order

Okay, let’s move on to the book itself, and something a bit less intellectual as a palate cleanser: The Reuschel brothers card (page 64). Holy cow. Putting aside the brotherly love angle, one look at those two and I feel that anything is possible for anyone. Is this one of the feel-good cards of all time?

They certainly don’t look like models for classic Greek statuary, do they? In point of fact, of course, they were elite athletes, and Rick in particular had a career that reveals itself to be, in the light of the newer, more accurate statistical analysis, right up there with some borderline Hall of Famers. He was also a good hitter and, despite his seemingly doughy recreational bowler’s build, also occasionally used as a pinch runner. But the two of them together make quite a picture, especially with the added Topps imperfection of the card–their names are reversed. This homely, glitch-filled world is the beautiful world of my childhood in the 1970s, and I miss it.

The Dick Sharon chapter (page 77) is one of the most moving, closing on you with your father talking about his father. “… His voice trailed off. He was thinking, remembering, carefully choosing what to pass on to me. I leaned close. I saw a little boy holding his father’s hand, bathed in light.” Do you get to that particular story of your father and grandfather without the Dick Sharon card? How much of your memoir is dependent on a particular card existing, and how much was going to make it the book in no matter what?

The Dick Sharon card and more generally the format of this particular book certainly shaped the way that story came out of me, but that was a story that I have told before in other ways. In the novel I was working on for years before I turned my full attention to my baseball cards, there’s a long chapter in the voice of a character based on my father in which he talks about his own father, among other things, and much of the material of the Dick Sharon chapter is touched on in that section of the novel, though via a different approach and with different levels of emphasis.

Sometimes leaning on my cards draws things out of me that I am otherwise unable to get at, and other times leaning on my cards gives the obsessively told and retold stories of my life a buoyancy and balance that they may have been lacking. Also, I may have had and may still have the tendency in my writing to try to absent myself from whatever I’m writing about, partly in an impossible reach toward “objectivity” and partly in an unconscious hunger for the painlessness of self-abnegation; the cards pushed back against this tendency, always inserting my messy self squarely in the middle of any story I could hope to tell.

At the end of Kent Tekulve (page 128), you talk about the “fantasy of all real loners: that one day the world that has shunned them, and that they have shunned, will come to them desperate for help. And that they will then stride to the very center of the predicament and, despite their thick glasses and bulging Adam’s apple and mathematician wrists and ungainly, unmanly submarine delivery, earn widespread grateful weeping adoration for extinguishing the dire threat and saving the day.” Okay, maybe Cardboard Gods hasn’t saved the world, but on some level, does it feel at all like that fantasy has come true for you?

I don’t know about that, but what I can tell you is that I’ve gathered more evidence over the past few weeks that I’m on some level addicted to being miserable. It’s like that scene in “Crimes and Misdemeanors” right after Woody Allen’s character finds out he doesn’t have cancer. He’s shown on the street, in his first private moment since getting the news, and he sort of awkwardly exults a little, and then almost immediately hunches over again, brow furrowed, thinking about the next potential calamity, or perhaps about the fact that he’ll die soon enough anyway, one way or another. When the book got published, I vowed I’d never complain about anything ever again, but as my poor wife can attest I have found plenty of ways to complain and worry and moan. Part of these worries grew out of the good feeling I had during a brief east coast book tour, during which I got to cast aside my loner persona and be a social being for once. I worry about the inevitable end of the good feeling, and I also worry that by enjoying that feeling I have betrayed my true loner self and will never be able to write a decent sentence again. I’ve got all the bases covered! I’m not solely a miserable guy, though, I hope, or at least I can say that I have truly been very grateful to hear from people who like my book. I just got an email from a soldier serving in Afghanistan who told me he got the book in a care package from his wife and enjoyed reading it. That’s the kind of thing that can cut through even my thick armor of habitual self-centered misery.

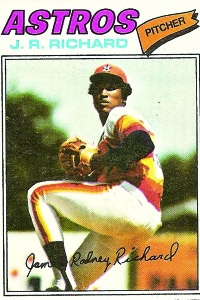

What a story: J.R. Richard

J.R. Richard chapter (page 214): “By the time I began hurtling down the bumpy, deceptively steep incline, Bill had wrenched his own bike to a halt and was running toward me and shouting at me to try to do the same. I didn’t see him, and anyway it was too late. The handlebars had turned into a jackhammer. I was going too fast to think. Ten seconds into my mountain-biking career I flew off a cliff.”

I’m trying to decide if you’re the stroke-cursed J.R. Richard in this moment, or if you’re the Houston Astros cluelessly ignoring the warnings of potential death. In any case, my question is, “Dude – what the hell?”

The connections between this version of my life story and a particular baseball card are sometimes pretty allusive. I guess it depends on the reader whether the connection will seem valid. One reviewer singled out my chapter on Jose Morales as containing too much of a stretch between an element of the card and an element of my life, but two other reviewers singled out the same connection for praise. As for J.R. Richard: He generally provided a way for me to meditate both on the feeling of drifting farther and farther away from the exciting, colorful world of my childhood and and on the feeling of just being generally adrift in adulthood, a feeling that has some illusion of safety in it – you get the feeling you can drift forever – until you, say, have a stroke or fall off a cliff.

I didn’t mean I couldn’t see the connection. I just meant … Holy cow, you nearly killed yourself!

Right! Yes, I am very lucky. No helmet, no forethought, no experience. This is why I spend my free time in libraries. I am not so good at navigating the world.

I could keep asking you questions on this book for quite some time, but this seems like a good place to wrap things up. So I think my final questions are these:

What are your plans now?

What’s the old Yiddish saying? Man plans, God laughs? Something like that. (I think it rhymes in Yiddish, so it’s a little catchier.) It’s a nice saying to lean on for a guy like me who has always had a profound aversion to planning. Speaking of Yiddish, I just learned from my cousin, in an email she wrote me after finishing reading my book, that our grandfather, my father’s father, an immigrant from Galicia who as I mention in the book died under somewhat mysterious circumstances way back in the 1930s, at one time in his life played the violin. By the time my father, the baby of the family, came along, the violin was gone, probably sold for some much needed money. My cousin’s mother, my aunt Helen, didn’t remember my grandfather playing the violin either, but apparently at some point, before his sad new life in America overwhelmed him and made him into a silent, unemployable, brooding figure in the tenement apartment, he knew how to produce music from that violin. Like Roberto Benigni’s character says in Down By Law, it’s a sad and beautiful world. What is there to do but try to find that music?

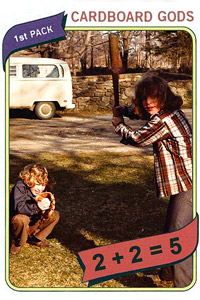

The Wilker brothers, in no particular order

Looking back, aside from where they have taken you in your writing, how have baseball cards impacted your life, as far as your relationships with your family, your emotional self or anything else?

My baseball cards, whew. At this point that’s like asking what impact air has had on my life. Maybe I can move toward an answer by trying to recall what kind of space they took up in my life when I was in my early to mid 20s. At that point, I’d been away from them for many years. I hadn’t touched them or seen them for a long time. They were in a storage facility hundreds of miles from where I lived. I knew even then that they were personally valuable, that someday I’d get my hands on them and bring them back into my life. I had a sense that they were something that was missing.

You feel like something is missing, maybe you start praying to something. The cards have worked pretty well in that respect. They help me feel connected to my past and to my loved ones, and they help me get through the day.

Comments are closed.