It’s impossible for a baseball fan like myself to be blindsided by the news that a ballplayer staring at his 40th birthday, with 3,166 hits already in his back pocket, is retiring.

And yet, when I saw on Twitter at 7:15 a.m. today that the great Adrián Beltré has called it a career, my gut got punched in a way that I was totally unprepared for.

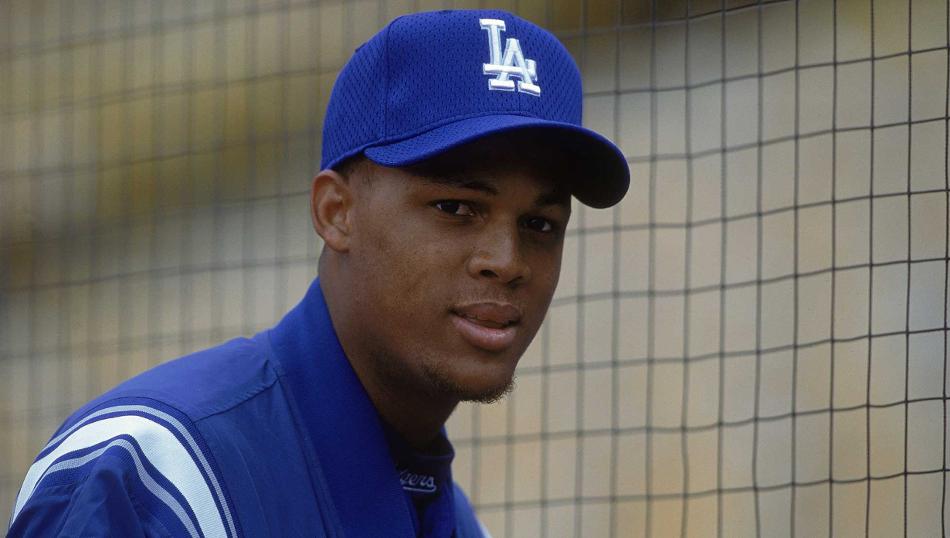

It has been 14 years since Beltré last played for the Dodgers — twice as long as his actual time in Los Angeles — which is plenty of time for me to outgrow my allegiance to him. But that never happened.

Beltré made his Dodger debut three months before I met my wife. He is retiring with my oldest kid a year and change from going to college. Beltré is, in the field where I have so long looked for comfort and catharsis, one of the final bridges between a single life that I had come to detest, and the life I have come to so appreciate now.

In particular for fans of the Dodgers, Beltré represented hope in one of their most depressing seasons. It was, in fact, the 1998 multi-player trade sending Mike Piazza away that upended the Dodgers and dominoed into a spot in the lineup for the 19-year-old Beltré to take. He wasn’t ready, per se, but for these sore eyes, he was ready enough.

I won’t take the time here to go through Beltré’s Dodger career in detail. There were steps forward and steps back, complicated by an emergency appendectomy in 2001 that could hardly have gone worse, except that he survived. In the summer of 2002, it was common for always impatient Dodger fans to believe that this prodigy needed the midseason acquisition of Tyler Houston to motivate Beltré. In April 2003, when he was just turning 24, I had to remind Dodger fans not to give up on him.

Then came 2004, when Beltré burst forth in supreme glory, unconscious at the plate, seemingly enhanced by a bone spur in his left ankle that restricted him just enough from diving at the low and outside pitch. Beltré had 48 home runs, 200 hits, an OPS over 1.000, and of course the sterling defense that is his ultimate calling card. In a Barry Bonds-less world, Beltré was the National League Most Valuable Player.

Beltré had 147 career homers at the age of 25, more than anyone in Dodger history — 38 more than Duke Snider.

And then he was gone. Years after Paul DePodesta and the Dodgers parted ways, years after infusing the front office with a Moneyball approach seemed like a radical idea, the lingering controversy over DePodesta’s two-year tenure as Dodger general manager is the circumstances of Beltré signing with Seattle as a free agent. For what it’s worth, DePodesta explained it to me thusly in this interview.

Of course, not every dream DePodesta and the Dodgers have will come true. Asked what his biggest disappointment from the 2004-05 offseason was, DePodesta didn’t hesitate to say it was the loss of third baseman Adrian Beltre as a free agent.

“It’s Adrian,” DePodesta said. “There’s no doubt. There were a lot of guys we pursued and would have loved to have had, but when it’s one of your own who had a breakout year, in the prime of his career – that’s an easy answer.”

While DePodesta regretted the outcome, he said that there was nothing the Dodgers could have done differently to keep Beltre. Though this could not be confirmed with Beltre’s agent, Scott Boras, DePodesta said that it’s “very unusual in a free-agent situation to have the ability” to meet directly with the player. Everything had to go through Boras – not that DePodesta was blaming Boras in any way.

“I certainly had a lot of contact with Scott,” said DePodesta, who was also interested in other Boras clients including Hernandez, Derek Lowe and Alex Cora. “Three to four face-to-face meetings, lots of phone calls. … Scott was on my speed dial throughout the winter. There certainly wasn’t a lack of communication there.”

Conversely, there was one meeting with DePodesta, Boras and Beltre in the same room.

“Even in that meeting with Adrian, it was forbidden to talk about financials or contract,” DePodesta said. “We could just talk about the team.”

The bidding on Beltre between teams was not a back-and-forth, can-you-top-this contest, according to DePodesta, but more of a blind auction. DePodesta told Boras to contact him when he was ready for their offer, and so he did. And ultimately, the Beltre camp liked Seattle’s offer better.

Some thought DePodesta’s offer was generous; others might argue that DePodesta should have found a way, despite all the obstacles, to make the Beltre signing happen. Whether he could have or not, what was immediately clear was that the Dodger winter was headed for rewrite.

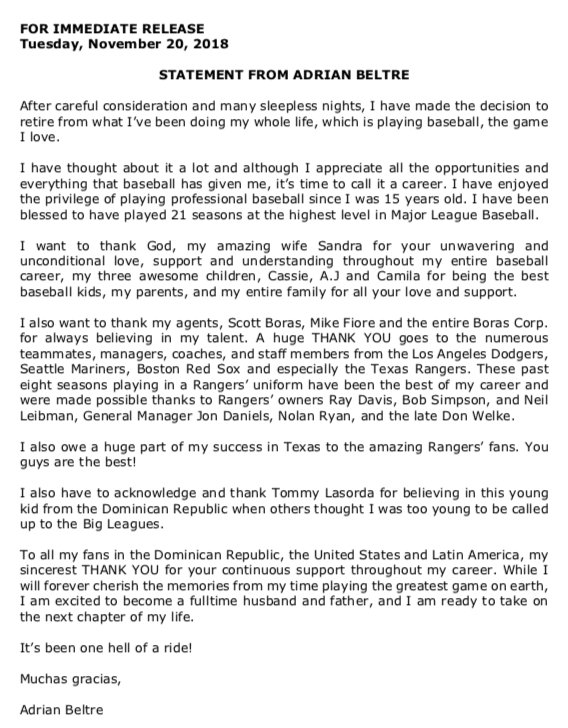

As it turned out, Beltré found the hitting environment in Seattle challenging, and in the prime of his career posted the worst numbers of his career. In compensation, he spent his final decade hitting in Fenway Park and Arlington, where his offense sizzled and his defense earned the appreciation it always deserved. Including walks, Beltré compiled more than 6,000 bases in his major-league career, yet his signature will be his virtuosity in charging a bunt toward third base, barehanding the ball off the grass and throwing out the vexed runner at first.

By the time his career was winding down, Beltré had become one of the most popular players around, a player whose joy and quirks — don’t touch his head! — never failed to make you smile. He will go into the Hall of Fame with a Rangers hat on his plaque, but he belongs to baseball.

And he’ll always have an important place in my love of the game.

Comments are closed.