Month: October 2010 (Page 1 of 4)

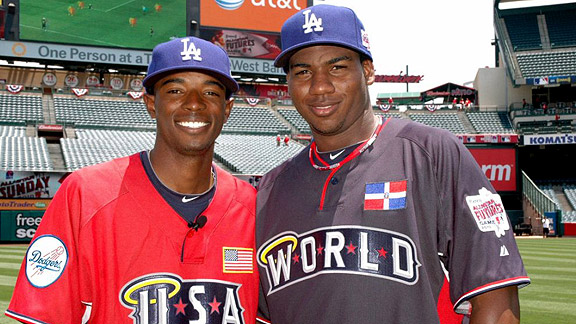

Ben PlattDee Gordon with fellow Dodger minor leaguer Pedro Baez at this summer’s Futures Game.

Dee Gordon might make it to Los Angeles someday, but we’re going to have to get him out of Puerto Rico first.

Gordon was late for my phone interview with him Friday night – and greatly apologetic – but he had good reason. The Dodger minor-league shortstop, and by some accounts the top prospect in the organization, was busy going 4 for 5 in Gigantes de Carolina’s 11-10 marathon victory over Leones de Ponce in the Liga de Beisbol Profesional de Puerto Rico – a night that raised his Winter League batting average to .654, thanks to a sizzling 17-for-26 performance.

Gordon, 22, has eight hits in his past nine at-bats, 11 in his past 13 and six consecutive multihit games overall, so it’s safe to say he’s finding life in the territory to be pleasant. It’s the first time in his life that he’s been out of the continental U.S.

“I love it. I’m with some great teammates that are taking very good care of me,” Gordon said, citing Antoino Alfonseca and Valerio de los Santos (both 38) in particular. “They’re making my time here great. … They making everything easy, showing me the right thing to do, looking after me. It hasn’t been really difficult at all, because these two guys have helped so much.”

Gordon, of course, isn’t there for the sightseeing. Rated the No. 1 prospect in the Dodgers’ farm system by such sources as Baseball America and Baseball Prospectus last winter, and said to have Gold Glove potential by Keith Law of ESPN.com, Gordon was given a full season in Double-A with Chattanooga in 2010. In some ways it was a success – batting .277 in a Southern League known for its pitching, while leading the league in at-bats and steals, but he still showed the rough edges to his still-developing game. For comparison, he had almost as many errors (37) as walks (40).

Not surprisingly, Gordon said that his on-base percentage – “trying to walk a bit more” – and his defense were among the principal areas he is focusing on improving in Puerto Rico, along with his “mental maturity.” Dodgers minor league hitting instructor Gene Clines has been working with Gordon on working the count, and though Gordon has walked only once in Puerto Rico, he said the lessons are taking hold.

“I’m definitely seeing way more pitches than I ever seen in my life,” said Gordon, whom the Dodgers took in the fourth round of the 2008 draft. “I’ve been working on that since the last bit of the AA year. That’s something I’ve been working really hard. … As a leadoff guy, you’ve got to (be able to) hit with two strikes, just not panic.

“I would hack at the first thing I saw and get myself out. I’m actually giving myself a better chance to hit. I may not be walking as much, but I’m actually seeing pitches that I can hit and drive.”

On defense, Gordon partly blamed a lack of concentration for his high error totals.

“Sometimes I feel if I get lackadaisical, sometimes that does (affect the defense),” Gordon said, “but I’m getting better in that. Not taking any pitches off, just locked in and ready to play.

“You should be focused every play of every game. … If your mind ain’t right, you won’t be able to catch the ball anyway.”

Though Gordon said he sometimes got down on himself in 2010 because he has high expectations, he subscribes to the belief that you need those struggles to learn the game.

“I still may swing at a bad pitch, still might make a bad decision on defense,” he said. “That all comes with learning. If you don’t mess up, you don’t learn.”

Gordon, who many are hoping also adds some mass to a slight frame (officially listed at 5-foot-11, 150 pounds), should likely begin 2011 with Triple-A Albuquerque, which happens to have a vacancy for a starting shortstop. There, he will probably play alongside second baseman Ivan De Jesus, first baseman/outfielder Jerry Sands and Gordon’s close friend, outfielder Trayvon Robinson. That would put Gordon within striking distance of the majors – and with injury-prone Dodger shortstop Rafael Furcal’s contract expiring at the end of 2011, the timing couldn’t be better – but Gordon said he can’t taste the show yet.

“There’s a lot of work (to do),” he said. “I can’t taste anything – I’m not there. There’s nothing I can taste. I haven’t played a day or an out or an inning in the majors. I’m a minor-league player, working to become a major-leaguer. That’s all I can do, and that’s all I can be.”

* * *

Gordon has a Twitter account where he aims to interact with fans when he can: @deegordon.

* * *

Dodgers manager Don Mattingly has caught some undeserved grief in the past 24 hours or so because his Phoenix Desert Dogs team in the Arizona Fall League ran out of pitchers and couldn’t finish the nine-inning game, as Scott Merkin of MLB.com reported.

As someone who wishes the next Dodger manager had more experience, I nevertheless found this to be completely unremarkable. Some people have been using it to launch more snark at Mattingly, but that snark betrays a lack of understanding of what the AFL is – a series of games designed to provide a limited number of players with practice in a (pseudo-)competitive setting.

The math is simple: Mattingly was given five pitchers to work with Thursday (two others were injured), and was expected to get them all in the game while adhering to strict pitch-count limits. Over the first six innings he used three hurlers, none of whom pitched all that well, leaving him with two for the final three.

The real trouble began with Dodger prospect Steven Ames, a 17th-round pick in 2009, couldn’t retire any of the seven batters he faced in the seventh inning. The next pitcher, Marlins prospect Steve Cishek, fared little better, retiring only two of the next seven batters, using 36 pitches in the process.

That forced Mattingly to use a sixth pitcher, Braves prospect Cory Gearrin, who was supposed to pitch today, in order to complete the seventh inning Thursday.

Tony Jackson of ESPNLosAngeles spoke to Mattingly today and sent along these quotes:

“You only have so many guys, and we have two starters down (with injuries),” Mattingly told Jackson. “Each organization dictates how much you can use their guys and how much they can pitch. Ames just got here, and he was only supposed to go one inning or 30 pitches. And then Cishek, he could only go 40 pitches or two innings. And then I had to bring in Gearrin, and he only had 14 pitches left.’

“This had nothing to do with managing a game. I would do it every day exactly the way we did it, because I’m not going to send somebody out there and get them hurt, either somebody from our organization or from another organization. And you’re not about to send another (position) player out there (to pitch) and risk getting them hurt just to get through one inning. … We saw this coming for three or four days. We’d send a guy out there and cross our fingers and just hope he could give us an inning or get a double play or whatever, just to get us through. But it finally caught up with us.”

It’s happened before, and it’s happened again. Save the grievances about Mattingly for when they actually matter …

Folks are starting to wonder – perhaps for lack of a better solution elsewhere – whether the Dodgers might be able to help themselves from within next season.

In addition to Jerry Sands, there are signs of life from second baseman Ivan De Jesus, writes Mike Petriello of Mike Scioscia’s Tragic Illness. De Jesus, trying to recover from a somewhat disappointing 2010 (that followed his broken leg from 2009), is at least putting his best foot forward in the Arizona Fall League. Another infielder, Dee Gordon, is on a similar path – tearing it up in winter ball in Puerto Rico to the tune of 13 for 21.

Then there’s outfielder Trayvon Robinson, who is turning heads in the AFL – most notably the head of Dodger manager Don Mattingly, writes Jason Grey of ESPN.com. Robinson is actually coming off a fairly productive season – .404 on-base percentage (73 walks) – in the Double-A Southern League, where pitching is known to dominate. Mattingly has been impressed by Robinson’s development, though not surprisingly, the manager is hesitant about the idea of jumping the player straight to the majors from AA.

I don’t know that the Dodgers would or even should assume any of these four could start for the team next season, so I’d expect the front office to operate during the offseason as if they won’t. But if even one of these guys can step up by midseason, it would provide a big boost.

I’ve been noticing a number of San Francisco Giants fans online who either a) are looking to rub in their World Series appearance and potential title on Dodger fans or b) seem annoyed that Dodger fans haven’t given the Giants enough credit.

I say this from the most sincere and truthful place that I can: In all the times the Dodgers have been in the playoffs in my lifetime — 1974, 1977, 1978, 1981, 1983, 1985, 1988, 1995, 1996, 2004, 2006, 2008 and 2009 — I never once gave a thought to how Giants fans felt about it.

Getting to the playoffs and sometimes winning the World Series wasn’t about sticking it the Giants. It was about getting to the playoffs and sometimes winning the World Series. When the Dodgers popped the champagne in ’81 and ’88, it wasn’t, “Take that, Giants!” That wouldn’t have even occurred to me. It was, “We are the champions, my friend.”

San Francisco, you deserve congratulations for your great season. But at this point, it has nothing to do with the Dodgers. Most of you probably realize this, but if you’re a Giants fan thinking about Dodger fans this week, I promise you, your attention is in the wrong place.

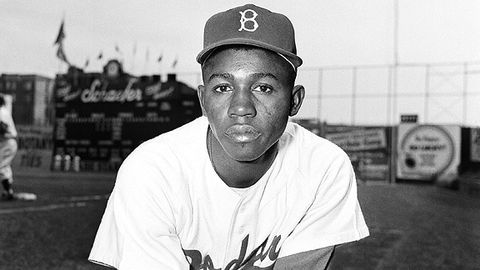

APJim Gilliam spent 25 years – half his life – in a Dodger uniform.

Keeping with this week’s theme …

Game 1 of the 2010 World Series almost exactly matched the final score of Game 1 of the 1978 World Series. That was Dodgers 11, Yankees 5, and it was played the night the Dodgers, for the only time in their history, retired the number of a non-Hall of Famer.

Jim Gilliam had passed away two nights earlier, barely 24 hours after the Dodgers won the National League pennant.

From Ross Newhan of the Times:

Throughout the playoff victory over Philadelphia he was driven by the memory of his relationship with Jim Gilliam, saying he had never before reached such an emotional peak, that when he went to the plate he could hear Gilliam speaking to him.

Davey Lopes, the Los Angeles captain, again resembled a man possessed Tuesday night at Dodger Stadium as the Dodgers, dedicated to sustaining the memory, crushed the New York Yankees, 11-5, in the inartistic opening game of the 75th World Series.

Lopes, who batted .389 against the Phillies, hitting two home runs while driving in six runs, ripped a two-run homer in the second inning and a three-run homer in the fourth, propelling the Dodgers into a lead that was 7-0 before Tommy John permitted his first run. …

The flags in center field were at half-staff and the game began only after the crowd was asked to join in a moment of silent meditation. The Dodgers carried a memorium to Gilliam on the sleeve of their uniform, a black patch with Gilliam’s No. 19 embossed in white.

“We dedicated the pennant to Jim,” manager Tom Lasorda said, “and we are determined to dedicate a world championship to him.” …

“Jimmy is up there watching us,” Lopes said following Tuesday’s victory. “His spirit is in each of us. The Yankees beat 25 guys last year and this year they’ll have to beat 50 of us. We’re going to do our damndest to win this for him and we’re confident we will.”

Things only became more emotional the next day. “On the afternoon of October 11,” I wrote in “100 Things,” “with Game 2’s first pitch hours away, baseball paused and gathered at Trinity Baptist Church to pay their respects – 2,000 strong – at Gilliam’s funeral. A memorable photo from that day shows Dodger tormentor Reggie Jackson of the Yankees standing solemnly between Lopes and Tommy Lasorda. All three delivered eulogies.” That long day’s journey into night ended with Bob Welch’s legendary triumph over Reggie Jackson for the final out.

From “100 Things”:

Clinging to a 4-3 lead in the top of the ninth, the Dodgers sent out Terry Forster for his third inning of work. Yankee playoff hero Bucky Dent opened the inning with a single to left field and moved to second on a groundout. A walk to Paul Blair put the go-ahead run on base, signaling that Forster had passed his expiration date.

Lasorda’s do-or-die replacement had 24 career appearances, 11 in relief. The two batters he needed to get out, Thurman Munson and Jackson, had 465 career home runs – three of them hit by Jackson in the last game of the previous year’s World Series. Dodger fans at the stadium and across the country waited for the roof to cave in.

Welch fed a strike in against Munson, who hit a sinking drive to right field that Reggie Smith caught at his knees.

APSteve Yeager is triumphant as Reggie Jackson strikes out.It was Jackson time. This wasn’t just any slugger. This was the enemy personified, a man, though well-liked in his later years, considered perhaps the most egotistical, vilifiable ballplayer in the game.

Welch began by inducing Jackson to overswing and miss. With Drysdalesque flair, he then sent in a high, tight fastball that sent Jackson spinning into the dirt.

Jackson later told Earl Gustkey of the Times that he was expecting Welch to mix in some of his good offspeed pitches, but instead came three fastballs, each of which were fouled off. Then there was a waste fastball high and outside to even the count at 2-2.

After another foul ball, another high and outside fastball brought a full count. The runners would be moving. Short of another foul, this would be it.

As everyone inhaled, in came the heat. Amped up, Jackson swung for the fences – not the Dodger Stadium fences, but the fences all the way back in New York.

Only after Jackson missed the ball and nearly wrapped the bat around himself like a golf club, only through Jackson’s rage, could Dodger fans begin to comprehend what happened.

Jackson carried his fury into the dugout and clubhouse with him, pushing first a fan on his way to the dugout and then Yankee manager Bob Lemon once inside.

The only thing that could have made the event better for Dodger fans would have been for them to have had longer to enjoy it. The Dodgers didn’t win the World Series that year; they didn’t win another game. Welch himself was the losing pitcher in Game 4, allowing a two-out, 10th-inning run in his third inning of work, and gave up a homer to Jackson in Game 6. But for a moment, the Dodgers and their fans enjoyed one of the most triumphant and exhilarating victories over the Yankees ever imaginable.

There probably hasn’t been a more emotionally charged Los Angeles Dodger team in history. That includes 1988. This was a team that had revenge and redemption on its mind all year, feelings that were only intensified by the passing of their beloved coach.

And they fell in their next four games – a 5-1 Game 3 loss, the bitter 10-inning, Game 4 defeat that starred Jackson’s moving hip, and then the final two games by a combined 19-4.

Sometimes, the stars seem aligned; sometimes, you have every reason to believe. And sometimes you lose, even when you leave everything you have, absolutely everything, on the field.

Craig Calcaterra of Hardball Talk has details on the motion filed by a Texas lawyer to request a continuance so that he could attend the World Series — make sure you click through to read the official papers. The wheels of justice do turn.

Bryan Smith of Fangraphs is at the Arizona Fall League, and shared these impressions of Dodger minor league player of the year Jerry Sands:

… I try not to be results-based in my batting practice “scouting” analysis, but it’s a lot more art than science, and I’m no expert.

Which brings me to an interesting scouting conundrum that popped up today, seeing the Phoenix Desert Dogs take batting practice for the second consecutive day. If you used just those two days, and those 40 swings, to make completely definitive judgments about players, there’s no question you would arrive at the fact that Austin Romine has more power (be it raw or present power) than Jerry Sands. The person who saw just 40 swings would, trust me, be shocked to learn that Romine hit just ten home runs this year where Sands hit 35.

You would be shocked because they have taken totally different approaches to the batting cage over the two days. For Sands, the focus has been hitting the ball the other way. At first, I thought maybe Sands was primarily an opposite field hitter, but given the sheer number of balls he’s hit towards right field in two days, I’m convinced it’s the orders he was given by the Dodgers. This is a guy not out there to show that he can hit the ball 400 feet, but working on improving his game by spraying balls around the park.

If you read the whole post, you’ll see Smith was less impressed with Dodger minor-leaguer Matt Wallach.

In game action, Sands has a .484 on-base percentage and .417 slugging percentage (no homers) over 31 plate appearances, with only four strikeouts. From what I can tell, reports of Sands getting a lot of time at third base have been overblown.

Ivan De Jesus, Jr. has a 1.076 OPS, while Trayvon Robinson is at .971. On the mound, Javy Guerra and Scott Elbert have each allowed a run in four innings. Elbert, whom it appears might be converted to relief for good, has had better control his past two outings.

* * *

On the anniversary of a divorce, Josh Fisher writes: “Jamie McCourt filed for divorce a year ago today, and we cannot say it’s been a banner year for the organization in any way. Not on the field. Not in the newspapers. Not on the farm. The Dodgers will be back, of course. You just can’t keep a club with its built-in advantages down forever. But we will spend the next months (but hopefully not years) determining whether the club moves forward under McCourt direction or otherwise. Still, if nothing else, the McCourt divorce stands out as another unfortunate example of what happens when everything that can go wrong…well…does.”

In the wake of the Yankees’ elimination from the playoffs, Emma Span wrote the following at Bronx Banter:

… I think the tendency of fans — and certainly not just Yankee fans, but perhaps especially Yankee fans — to instinctively blame their own team after a loss, rather than crediting the opponent, is pretty interesting. Obviously not everyone does this, but as an overall fanbase mood I think it rings true, unless maybe some undisputed whiz like Cliff Lee is directly involved.

Setting aside for the moment whether or not it’s accurate or fair in a specific instance, what’s the psychological gain here? The outcome of any game depends on the combination of one team’s strength and another’s weakness, of course, and it’s often hard to disentangle a hitter’s success from a pitcher’s failure, or vice versa. How much of Colby Lewis’s kickass performance on Friday night was due to variables he controlled directly, and how much was due to the Yankees’ inadequate approach or execution at the plate? It’s not possible to tell precisely, although a lot of the newer baseball stats our SABR-inclined friends come up with are designed to help sort this out. And my first instinct, like many people in the bar where I was watching, was to yell “C’mon you useless #$&*s, it’s Colby Lewis” at the little pinstriped men on the TV.

I think in the end, it’s mostly about control: the idea that your team mostly controls its fate (like the idea that you yourself mostly control your fate) is generally preferable to the alternative. No one likes feeling helpless to change their situation. Everyone wants to believe that we’re in charge of how our lives turn out, not larger forces we can’t affect. And hey, if the Yankees lost because they failed, well then, they’re still better. They just didn’t show it. There must be something they could have done differently. …

Though it becomes even more New York-centric as it goes on, Span’s entire post is worth reading. I agree that fans have a tendency to turn on their team when things go wrong, out of a belief that the team should be better. No one likes to admit to limitations. To me, the 2009 Dodgers were a vintage illustration of this – even when that team was winning, the slightest, most momentary setback would send many fans into a tizzy. In my mind, that was a mistake. Yes, we all want to win, but losing shouldn’t mean the elimination of all joy.

It’s not necessarily a sign of weakness to tip your hat to your opponent. On some occasions, it could mean that you’re failing to look at your own inadequacies. But I don’t think that’s something Dodger fans are generally at risk of – quite the opposite. Every foible gets a thorough examination.

One thing that the McCourt controversy and the struggles of certain players did to the Dodgers this year, however, was make those limitations that Span talks about feel more real. Against our will, expectations have been lowered. It portends a sour 2011, though at least there’s this: There’s a lot more room to be pleasantly surprised.

* * *

- I could bring more nuance to this, but this talk of expanding baseball’s playoffs – I’m dead set against it.

- Life Magazine has released some previously unpublished photos from the 1955 World Series – check ’em out.

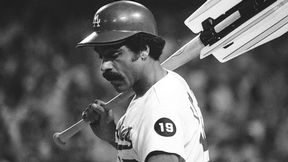

Focus on Sport/Getty ImagesNo. 6, Steve Garvey

The Dodgers, with only one exception, only retire the jersey numbers of Hall of Famers. So that’s why the 34 of Fernando Valenzuela doesn’t hang in the pantheon with Jackie Robinson’s 42, Sandy Koufax’s 32 and the like.

Valenzuela’s 34 is in unofficial retirement, having not been worn by a Dodger since the team released the lefty before the 1991 season, but “unofficial retirement” is as equivocal as it seems. Steve Garvey’s 6, for example, was unofficially retired for 20 seasons, only to be taken out of the safe for none other than Jolbert Cabrera in 2003. Since then, others to wear Garvey’s number are Brent Mayne, Jason Grabowski, Kenny Lofton, Tony Abreu and Joe Torre. (For that matter, the No. 6 was originally made famous for the Dodgers by Carl Furillo.)

I’ve never had a problem with the Dodgers’ retired-number policy, which was only ignored following the emotional passing of longtime Dodger player and coach Jim Gilliam during the 1978 playoffs. Ten numbers have been immortalized, and that has seemed like a plentiful number, one that spreads the honor around without diminishing it.

But over the weekend, I began thinking about the possibility that some of us might never see a Dodger uniform number retired again in our lifetimes. Think about it:

- Since Don Sutton reached the Hall and had his number retired by the Dodgers in 1998, the only likely future Hall of Famer to wear a Dodger uniform for more than a couple of seasons is Mike Piazza. Do you retire the number of a player who spent only seven years in Los Angeles?

- Oldtimers like Gil Hodges and Maury Wills have been trying to get in the Hall for years, to no avail.

- The only current Dodger whom one can even conceive of building a Hall of Fame career is Clayton Kershaw, but of course, odds that we’ll be attending his uniform retirement ceremony depend on him stringing together about 10 or more remarkable seasons without leaving Los Angeles.

Certainly, any year could bring a future Dodger Hall of Famer, but chances are strong that in, say, 2028, we’ll be marking the 30th anniversary of the last Dodger uniform being retired if the current policy remains.

So I just got to wondering whether it might be worth it to institutionalize a new era in retiring numbers. This is just brainstorming, but one idea I had was that every 10 years, one Dodger great who isn’t in the Hall would have his number retired.

I’m curious about what your thoughts are on this subject, and also – if, hypothetically, my idea came to pass, which number you’d like to see retired next?

Ron Vesely/Getty ImagesFernando Valenzuela

Fernando Valenzuela’s April and May in 1981 were something you felt inside you, like a superpower. And that’s just if you were a 13-year-old white kid in the Valley.

If you shared a common heritage with Valenzuela, as Cruz Angeles emphasizes in “Fernando Nation,” which premieres Tuesday on ESPN, Valenzuela’s arrival was like the birth of the Justice League.

Angeles’ documentary on Valenzuela has a lot of ground to cover – it won’t surprise Dodger fans how inadequate 50 minutes is to do the job – but he gets across the depths Valenzuela rose from, the heights he soared and the impact he had on people he didn’t know personally but who had a powerful connection to him.

The personal story of Valenzuela isn’t lost amid the bigger picture. “When I was a child, we didn’t have any dreams,” Valenzuela recalls in the documentary’s opening minutes. After Valenzuela became a sensation in 1981, KABC Channel 7 raced to provide the dusty reality of the remote Mexican village he was raised in, a world away from the United States. But rather than aimlessness, that absence of expectation sowed in Valenzuela a discipline. “I just wanted to get better, step by step,” Valenzuela remembers thinking, even in his pre-teen years.

But as Angeles takes pains to illustrate, Valenzuela wasn’t a mere mascot for the Mexican, Latino or Chicano communities. He was something cathartic, something euphoric, to heel wounds that had been felt by some for decades.

Angeles mostly does well articulating the controversial displacement of the residents of Chavez Ravine in the 1950s, including the key issue of how the new public housing, playgrounds and schools that had been promised for that area as early as 1949 was eventually scuttled after one of its principal advocates, assistant housing director Frank Wilkinson, was swept up in the Red Scare. (Details of this are in Chapter 11 of “100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die.“) It can’t be emphasized enough that most of the damage to people in this area occurred before Walter O’Malley had even heard of it.

The narrative in “Fernando Nation” plays things a little looser after O’Malley gets involved, directly connecting him and the construction of Dodger Stadium with the forced evictions of the area’s remaining denizens, even though those evictions were in the cards regardless of whether the Dodgers ever left Brooklyn. It is documented that Los Angeles would act in broad strokes with the area (which it bought back from the United States, on the condition that it be used for a public purpose, after the public housing contracts were canceled). A baseball stadium was but one of multiple possible outcomes, all of which meant taking full control of the land.

Nevertheless, even if the fine print absolves the Dodgers of responsibility for what happened at Chavez Ravine, there’s no mistaking what the lingering perception was for many: Dodger Stadium was on their land. And the ill will, Angeles notes, only deepened with the rise of the Chicano (Mexican-American, to oversimplify) movement in the late 1960s. To make this clear, Angeles uses archived footage of police brutality at a Chicano rally, including a cop clubbing a female bystander in the back, that makes the Rodney King incident almost look like childs’ play.

Even after Fernandomania began, issues of ethnicity and nationality remained alive; Angeles includes a clip from “The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson” in which the host cracks with regard to the 1981 players’ strike, “Reggie Jackson offered Fernando Valenzuela a job as a gardener.” Valenzuela is later called in a news report “Mexico’s most documented migrant.” And when Valenzuela held out for a bigger raise during Spring Training 1982 (like Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale in 1966, or for that matter Zack Wheat in the Prohibition Era), a government official pointedly comments that Valenzuela is in the country on a restricted visa dependent on his employment.

At the Q&A that followed Thursday’s premiere screening, one audience member asked Angeles why he had to bring such negativity into the Valenzuela documentary, considering how positive an experience Valenzuela was. Angeles responded that he didn’t see his inclusion of the history as a negative, believing that by understanding it, you see even more clearly the wonder of Valenzuela’s impact. The history is something to embrace, Angeles believes. It’s why nothing will ever be like Fernandomania.

And certainly, there is no shortage of joy in the program, especially as Valenzuela runs off to his 8-0, 0.50 start in ’81. “It is incredible, it is fantastic,” Vin Scully gasps in wonder. “Fernando Valenzuela – he has done something I can’t believe he has done or anyone will do.” Dodger fan Paul Haddad, whose childhood cassette tapes provide much of the primary-source audio for “Fernando Nation,” comments that “I was getting to experience my own Babe Ruth.” Viewers of “Fernando Nation” will truly revel in Valenzuela taking the nation by storm.

If there is a negative that is glossed over in the documentary, it is how quickly Valenzuela came back from the stratosphere to become mortal. Everyone knows what Valenzuela did in his first eight starts, but in his second eight (the final two of those coming after the strike was settled), he had one victory and a 6.46 ERA, averaging under six innings per start. (John Ely, anyone?)

Of course, Valenzuela recovered to have more great moments (such as the 1981 World Series complete game, of which Scully said, “This was not the best Fernando game, it was his finest.”) and great seasons. Valenzuela was also a wonder with the bat and the glove as a pitcher. What you’re left with is the impression that has always been an indispensable part of the Valenzuela story: He had the goods – the tools, the preternatural ability to learn the screwball from Bobby Castillo, the determination – but worked to be great.

Because of the time constraints and all the time spent discussing the birth of Fernandomania, “Fernando Nation” races to cover the later years of Valenzuela’s career – and in its depiction of Valenzuela’s 1990 no-hitter, there’s an omission in the documentary that’s nothing short of startling. But the documentary is nonetheless a success, because it leaves you, once more, with that unbridled feeling of superpower coursing through you. Fernando Valenzuela, sweetness.

Giants at Phillies, 4:57 p.m.

* * *

Part 3 of Robert Whiting’s series on Hideo Nomo has been published in the Japan Times.

Yankees at Rangers, 5:07 p.m.

* * *

Fernando Valenzuela with Cruz Angeles (right)

OK, I’m just going to get this out of the way right now: Fernando smiled at me. I mean, he charmed the living daylights out of me.

Forgive me for acting like a lovestruck teen (or twentysomething, or thirtysomething … I’ve been through it all), but I mean, it was that nice a smile.

I wasn’t expecting it. I attended Thursday’s premiere screening of “Fernando Nation,” the ESPN “30 for 30” documentary directed by Cruz Angeles that will debut on the small screen Tuesday. Valenzuela was the guest of honor. After the screening, during the Q-and-A, I asked a question of the director that I really wanted to ask Valenzuela — in fact, part of the reason I asked was the hope that Valenzuela might step in and answer it. And he did.

The question related to how Valenzuela had handled the crush of attention that came during his rookie season and how he kept it from overwhelming him. Angeles first said he believes that Valenzuela’s family taught him the discipline to handle the challenge. Then, Valenzuela was handed the microphone. Here’s part of his response:

“I think when I decided to play this game, I knew a lot of things were going to happen,” Valenzuela said. “My first year with the Dodgers was the hardest year for me. I wanted to practice with the team; I wanted to be with the team. I wanted to just enjoy the game. … (But) I had it in my head that’s part of the game. I tried to do my best; I tried to take care of everyone.

“Also, I liked that year. That happens only once in life. It happened to me in ’81. I enjoyed it.”

As he answered, looking at me as he spoke, that was when that big smile came across his face. It didn’t have anything to do with me, it was just him enjoying the memory, or the moment of talking about the memory. But it really, really made me happy.

I don’t suspect I’m explaining this adequately. But I’m never going to forget that smile.

I’ll have more about the documentary in a separate post.

Trey Hillman, former manager of the Kansas City Royals and the only person I have ever interviewed between the hours of 2 and 5 a.m., is a “strong candidate” to become the Dodgers bench coach, reports Tony Jackson of ESPNLosAngeles.com. Mike Petriello of Mike Scioscia’s Tragic Illness offers the downside of this.