Quietly, Ron Cey thought he was a great baseball player. Why wouldn’t he?

Quietly, Ron Cey thought he was a great baseball player. Why wouldn’t he?

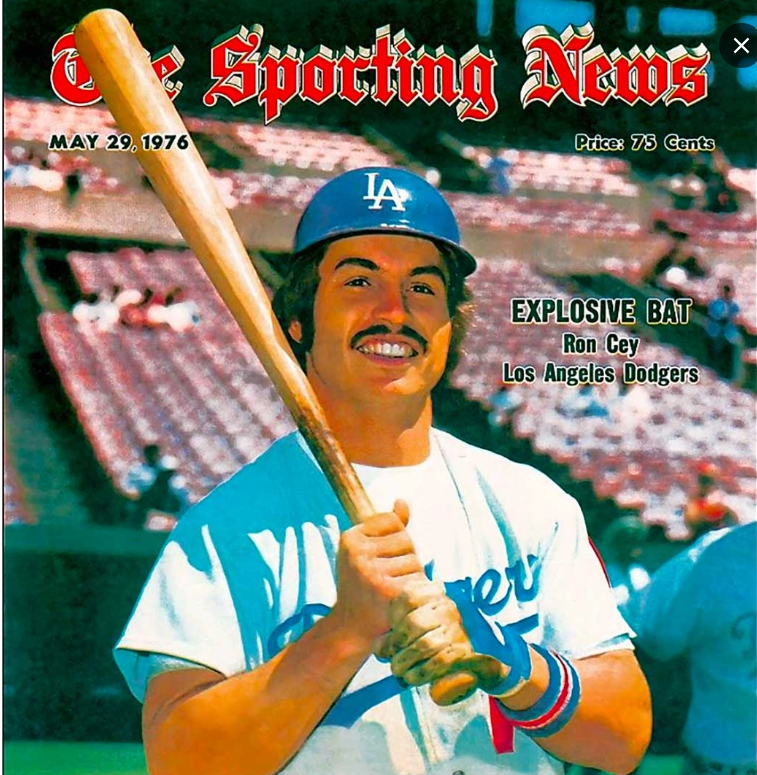

By the time he retired from the major leagues in 1987 after a 16-year career, Cey hit 316 home runs and 328 doubles. He drove in 1,139 runs. He scored nearly 1,000. If he wanted to get crazy, he could note that he walked more than 1,000 times and had an on-base percentage (you know, that elitist statistic) of .354.

Cey played in six All-Star games. He shared an MVP award for a World Series where his heroics were plain for anyone to see.

Arguably the best third baseman of all-time, Mike Schmidt, played in the same era as Cey. Another no-doubt Hall of Famer, George Brett, was the American League’s bellwether. After that pair, it would have been no crime for Cey to see himself in the hot corner’s highest echelon.

“Mike Schmidt was unquestionably the dominant NL third baseman from the mid-70s to the late ’80s, but Cey would have to be the No. 2,” wrote pioneering analyst Bill James.

Years later, fellow Dodger alum Tim Wallach introduced Cey to baseball’s statistical revolution, and it more than validated his inner beliefs. It exceeded them.

“Timmy came up to me one day when I was at the park,” Cey recalled in an interview. “He said, ‘I want to tell you that you are so much more valuable in our era of baseball than you were in your own.'”

Based upon wins above replacement, Cey is the No. 6 Dodger position player of all time, behind four Hall of Famers from Brooklyn (Pee Wee Reese, Duke Snider, Jackie Robinson and Zack Wheat) and the Californian who remains the franchise’s all-time hits leader (Willie Davis). Cey has the highest WAR of any Dodger position player of the past 50 years.

From 1970 through 1990, Cey’s WAR ranks 28th among all major-leaguers. Of the 27 ahead of Cey, 17 are in the Hall of Fame.

Of the 27 ahead of Cey, six are third basemen: Schmidt, Brett, Graig Nettles, Buddy Bell, Wade Boggs and Darrell Evans.

Of the 27 ahead of Cey, only two were Dodgers, both of them longtime American Leaguers: Eddie Murray and Willie Randolph.

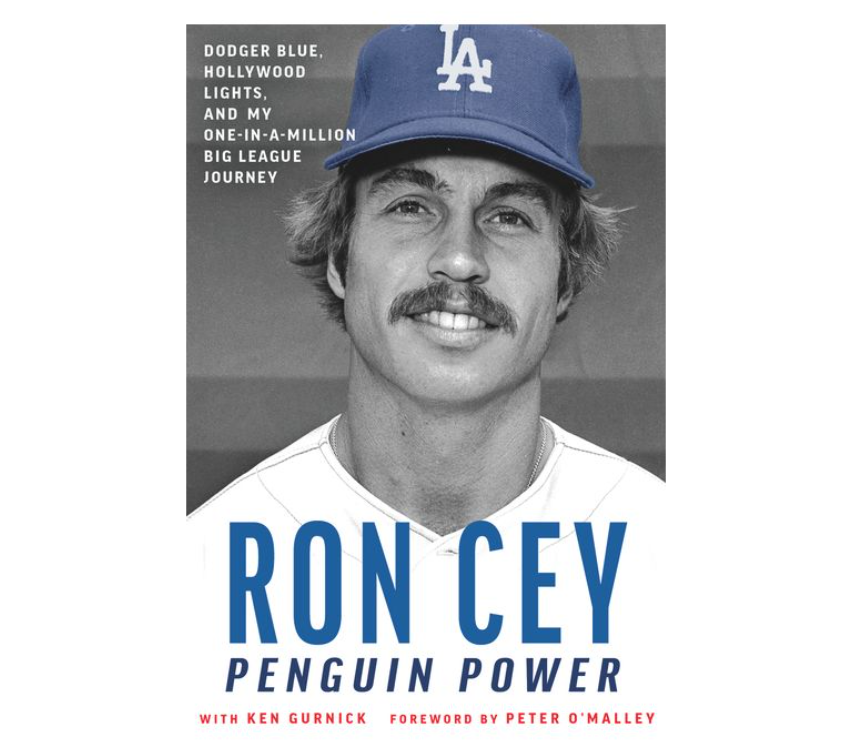

The title of Cey’s new memoir, written with longtime Dodger beat reporter Ken Gurnick, is Penguin Power. You can find the inspiration for that title in any number of chapters — not the least being an appreciation of a great nickname — but without a doubt, one of those inspirations is for contemporary fans to understand Cey’s powerful place in Dodger history.

“Just like I think that Dodger era didn’t get the credit it deserved for the things it accomplished, I don’t think Ron did either,” Gurnick said in an interview. “I think Ron’s right that he’s not in the top 1 percent of third basemen, but he’s probably right behind it. If you look at what he achieved through the prism of analytics … he did what they wanted him to do, and he did it really well in all phases of the game, and the numbers back that up.”

Perhaps more importantly, Penguin Power shares the stories behind that career in a breezy, invigorating style: not only Cey’s journey to greatness, but the incredible experiences he had along the way.

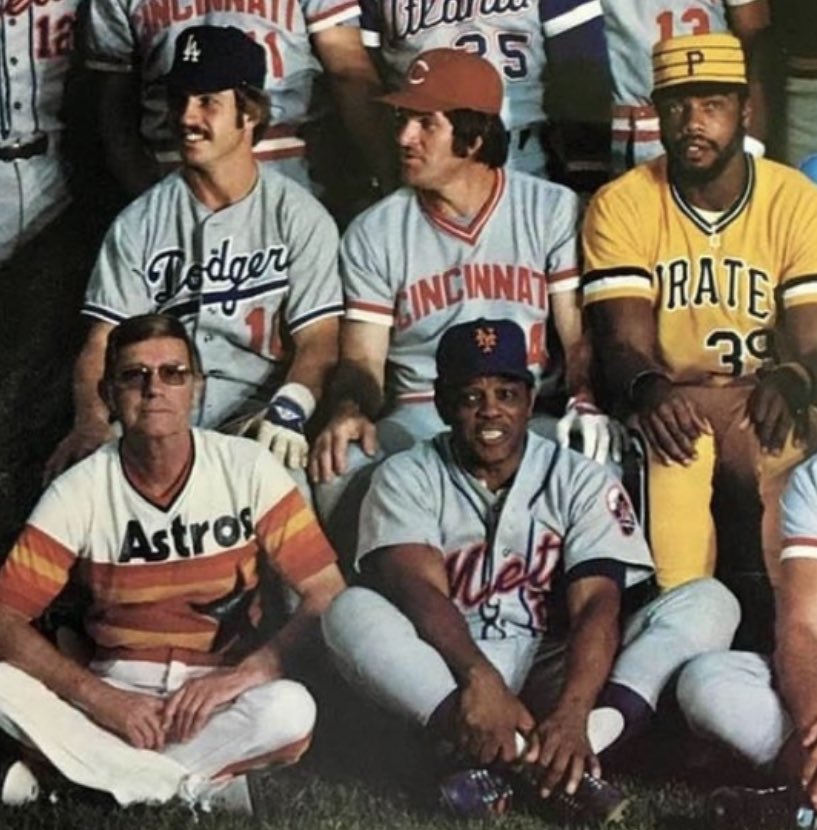

Two standout moments came at the outset of his Dodger career. Cey’s childhood idol — and a key motivator in his development — was Willie Mays. The 25-year-old Cey had a chance to meet him on June 9, 1973, but the circumstances were just a tad awkward.

Two standout moments came at the outset of his Dodger career. Cey’s childhood idol — and a key motivator in his development — was Willie Mays. The 25-year-old Cey had a chance to meet him on June 9, 1973, but the circumstances were just a tad awkward.

“Willie hit a home run,” Cey said. “As he’s coming around the bases, I have my glove in front of my face because I have a big smile on my face. I wanted to shake his hand, but I let him go.”

Cey was also playing third base on April 8, 1974, when Henry Aaron hit the record-breaking 715th homer of his career. Under the circumstances, it wouldn’t have been out of bounds to shake his hand — Dodger middle infielders Davey Lopes and Bill Russell did just that — but by the time Aaron reached third base, he was buffeted on either side by two barnstorming fans. Fortunately for Cey, he had more than enough time later in life to connect with these legends.

After his retirement, Cey also developed a finer appreciation for being part of MLB’s longest-running infield, which is being honored at Dodger Stadium on its 50th anniversary Friday.

“I think the impact of what we did wasn’t felt until after we were gone,” Cey said. “Years afterward, we started to piece back what we did. We were in the moment (while we were playing). We weren’t about to sit down and start praising ourselves. But we were more than just the longest-running infield in major-league history. When you look at the time we played together, we won a ton more games than everyone else did.”

Aside from winning the 1981 World Series, the peak of that era came in 1977, when the Dodgers banged out a 17-3 April. The team was a Ferrari, and no one drove it like Cey, who — in a formative experience for a 9-year-old fan from Woodland Hills — drove in 29 runs in 20 games while batting .425 with nine homers.

Only three other MLB players have driven is as many runs in a month in 20 games or fewer: Irish Meusel (1925), Dale Murphy (1985) and Ken Griffey Jr. (1996).

“We were on fire as a team,” Cey said. “This was the best month I had. It’s also chronicled factually that it’s the greatest month in Dodger history. My OPS was like 14-something (1.433).”

(Yes, even higher than Pedro Guerrero’s July 1985.)

“It was a great start for us, and a lot of guys were performing well. I just got this tunnel vision. There were absolutely no distractions. Everything was pretty much even keel. The first time up — boom — I’d hit a rocket somewhere. I’d drive in runs.”

While it’s one of the great nicknames in Dodger history, it’s been my concern that “Penguin” hasn’t helped Cey’s on-field legacy. I have feared the implication that it portrays him as something below par as an athlete, when the truth is the opposite.

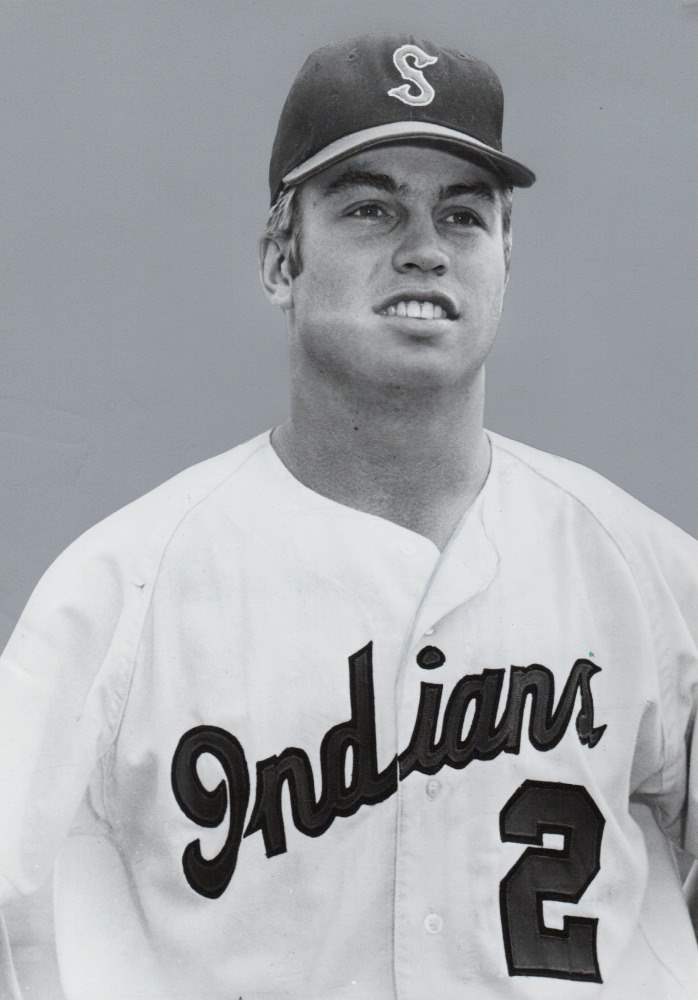

Cey disagreed, and to my pleasure, has never shied from the nickname, which he picked up at Washington State.

“I don’t think I was ever degraded,” Cey said. “It was just a nickname. The reason why I ran the way I did was because I hurt my right leg when I was playing Little League football at an early age. I let itself heel, so I was kind of dragging my leg. If this would have happened in today’s society, I would have gone to a person who would have got me in line and running.

“I know that the kids loved it. They called me the Penguin all the time. … People (have sent) me penguins from everywhere. I thought it was terrific.”

And even despite the injury, there was never any question of Cey’s athletic ability growing up — nor of how compelled he was to fulfill his goals.

“I could play every sport growing up, through high school,” he said. “I was an All-Star player on really good teams. I had this childhood dream when I was under 10 that I wanted to be a major-league baseball player. I knew even though I enjoyed others that baseball was my love.

“I was not getting knocked off my pedestal. I was continuing to be the better player, playing on teams, winning. The climb up the triangle was shrinking, and yet I was still climbing. I was finally reaching that point where ‘it’s getting really narrow here.’ You’re drafted, you’re playing professionally, you’re moving up the ladder. I just had this determination that I was gonna be that guy. I look back on it now, and I kind of laugh at it – a dream that became a reality that’s now a dream again. I never got knocked down hard enough where I needed to do something else.”

Penguin Power shows how Cey achieved no goal alone. Thousands of words are devoted to others, notably Peter O’Malley, Tom Lasorda, Marvin Miller and Bill Buckner (“He was a big part of my life,” Cey said of Buckner.)

One person Cey never took for granted was his wife, Fran. While he admits that his family could be dysfunctional like anyone else’s, the Ceys have been married for more than 50 years, a true rarity. Of the Dodgers’ core position starters in his era, Cey said he is the only one who remains betrothed to the same person.

“I had a very strong independent woman at my side,” Cey said. “Without her, this probably would have crumbled. When we took road trips back then, they were like 10 days to two weeks. After five years of playing in the big leagues, now we’ve got two toddlers (Daniel and Amanda) around the house. That just makes it really difficult. The stress is all on her. When you come back, you try to alleviate some of that — it gets back to a little more of a routine. But when you’re out of the house at 12 noon and home after midnight, that leaves a lot of burden at home. She’s a strong individual – if she hadn’t been, it would have been a real mess.”

If there’s one other thing the title Penguin Power might imply, it’s a certain level of irreverence. The 5-foot-10 Cey was a competitor, but his lighter side stood tall. If you’re not convinced, pull up a chair and listen to his songs, “One Game at a Time” and “Playing the Third Base Bag.”

Cey was spurred to take on both sides of a 45 by former Dodger Jim Campanis.

“We sort of did this for fun, but we kind of mocked it too,” Cey remembered. “I would say, ‘We sold 29 worldwide, and I have 25 in our house. … (But) they used to play this in Spring Training, both songs, as in-between inning entertainment. One day when my wife was in her group behind home plate, the lady behind her says, ‘Honey, is that Glen Campbell?'”

Cey keeps the great stories flowing in Penguin Power, but a simple message permeates the book. Take it as a reminder.

“If you have a goal, if you have dreams, follow your dreams,” Cey said. “If you have something that looks to be an impossible task, don’t let that deter you — if you have your mind on something and it’s a passion. Don’t be discouraged. Knock down some doors. Find out the answer to your own question.

“I’ve run into so many people who say, ‘I wish I would have done that.’ I didn’t want to be one of those guys.”

Comments are closed.