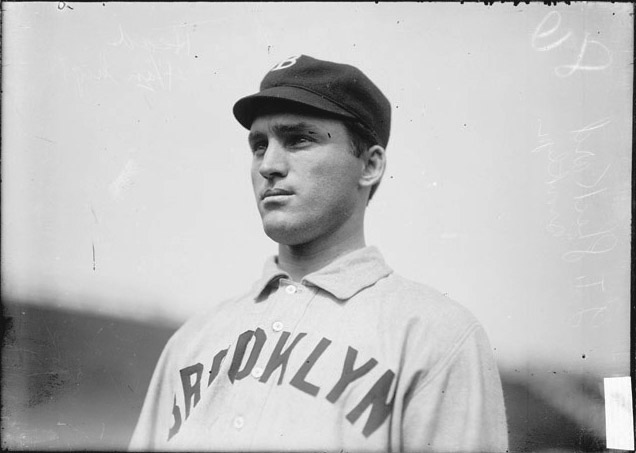

You might have heard Jimmy Sheckard’s name once or twice this summer, and even so, if you’re a Dodger fan under the age of 120, it was quite possibly the first time you ever heard it.

Largely forgotten among Brooklyn stars of the past, Sheckard hit three triples for the Superbas in one game on Opening Day 1901 at age 22, a feat that went unmatched until 23-year-old Yasiel Puig did so against the Giants on July 25.

That 1901 season was Sheckard’s best in a career that had more than a few highlights. Sheckard led the National League with 19 triples and a .534 slugging percentage, while finishing second in home runs (11) and total bases (296), third in batting average (.354) and OPS (.944), tied for third in RBI (104), fifth in runs (116), sixth in on-base percentage (.409) and stolen bases (35), seventh in doubles (29). In September, Sheckard also became the only player ever to hit inside-the-park grand slams in consecutive games.

Sheckard also had a run-in with an ump that surpasses any mess Puig has gotten into, according to Baseball Library.com:

In a 7-3 victory over the host Reds‚ Brooklyn’s Jimmy Sheckard is called out at 2B by umpire Cunningham — who is definitely having a bad week — and curses him so vehemently that he is slapped with a $5 fine by the ump. Cunningham returns to home plate and Sheckard follows‚ spitting in his face. Cunningham calls the cops and Sheckard is removed by the police. Cunningham later says‚ “I don’t know what kept me from pitching into Sheckard but if a player ever does that to me again I’ll pick up a bat and smash him. That’s the limit and the players can take warning.”

Despite his youth, Sheckard was in his fifth season in the NL by this time.

Samuel James Tilden Sheckard broke in at age 18 with the 1897 Brooklyn Bridegrooms by OPSing .976 in 49 plate appearances, then led the NL in steals at age 20 with 77 in 1899 during a brief detour with the NL’s Baltimore Orioles (in their final season before being contracted out of existence). No player under 21 has ever beaten that Sheckard stolen-base total.

Later, in 1903 with Brooklyn, Sheckard led the NL in both homers (nine) and steals (67), a feat matched since by only Ty Cobb and Chuck Klein, while reaching base at a .423 clip.

Sheckard had a massive decline to a .630 OPS in 1904, before rallying to a solid season in 1905. But that winter, Brooklyn traded Sheckard to the Cubs in exchange for Buttons Briggs, Doc Casey, Billy Maloney, Jack McCarthy and $2,000. None of the four players made particularly meaningful contributions.

In his first three seasons with the Cubs, Sheckard would play in World Series each year, with the Cubs winning their most recent two in 1907 and 1908. Sheckard went 0 for 21 in his first World Series, 5 for 21 in 1907 and again in 1908, and finally excelling 5 for 14 with seven walks in the 1910 World Series.

Sheckard played with the Cubs through 1912, leading the Majors in walks in his final two Chicago seasons (his 147 bases on balls in 1912 was an NL record until Brooklyn’s Eddie Stanky broke it in 1945), despite the following incident described by Jensen at the SABR Baseball Biography Project.

On June 2, 1908, Sheckard nearly lost the use of his left eye as a result of a fistfight with teammate Heinie Zimmerman. During the melee Jimmy threw something at the young infielder. Infuriated, Zimmerman picked up a bottle of ammonia and hurled it at his assailant. The bottle broke as it hit Sheckard between the eyes, spilling ammonia all over his face. (Frank) Chance ran to Sheckard’s assistance but Zimmerman had the best of the manager, too, until the rest of the team intervened. The Cubs originally tried to cover up the incident, but Sheckard was sidelined for several weeks and the story eventually leaked. Jimmy batted a career-low .231 in just 115 games that season (his fewest since 1900) but returned in time to participate in the famous 1908 pennant race. With regard to the Merkle incident, Sheck always claimed that his good friend Artie Hofman, the center fielder, should receive as much credit as second-baseman Johnny Evers because it was Hofman who alertly made the throw to Evers for the crucial forceout.

Another anecdote related by Jansen showed how Sheckard was arguably more colorful than Puig is today.

Thanks in large part to the writings of Ring Lardner, who was then a beat reporter covering the Cubs, Sheckard became well-known for his horseplay with Hofman and pitcher Lew Ritchie, with whom he formed three-quarters of a barbershop quartet (Jimmy sang baritone). The most famous example of his flakiness occurred in a game against Pittsburgh. After Pirate hitters had been spraying the ball all around him, a frustrated Sheckard stopped in the middle of left field, whirled several times, threw his glove up in the air, and went over to the spot where it landed. Orval Overall, pitching for the Cubs that day, couldn’t figure out why Sheckard was standing only a few feet from the left-field foul line and motioned for his outfielder to reposition himself. Sheckard refused. The next batter, Fred Clarke, hit a screaming line drive that went straight into Sheckard’s glove. Jimmy told teammates that the scheme changed his luck in the field from that day forward.

Ultimately, Sheckard finished his Major League career with 2,084 hits, 136 triples, 465 steals, a .375 on-base percentage and 121 career adjusted OPS. Believe it or not, he also still holds the NL record for sacrifices in a season with 46 in 1909.

He was named as the left fielder on the all-time Cubs team in 1962 by sportswriter Joe Reichler, notes Jensen.

Sheckard also was an outstanding defensive outfielder–both SABR and STATS, Inc., selected him to their retroactive Gold Glove teams for the first decade of the Deadball Era–and the right-handed thrower’s career assist total is one of the highest in history for an outfielder. One sportswriter described Sheckard as “a marvelous workman in his pasture and one of the surest, most deadly outfielders on fly balls that ever choked a near-triple to death by fleetness of foot and steadiness of eye and grip.” Another noted that he “did clever things in the outfield in nearly every game and was in a class by himself at trapping a ball.” …

… On a cold Sunday in January 1947, Jimmy Sheckard walked to his attendant’s job at a gas station directly across from Stumpf Field, the home of the Red Roses. As he limped toward the station (he suffered from arthritis in his left foot, which doctors believed was the result of an old baseball injury), a car struck him from behind and knocked him to the ground. Sheckard died of head injuries three days later. Umpire Bill Klem, who had called the balls and strikes in many of Jimmy’s games in the National League, presided over a ceremony in his honor at Stumpf Field, and the city of Lancaster erected a monument to his memory in Buchanan Park.

Thanks to Yasiel Puig for bringing Sheckard to my attention.

oldbrooklynfan

It’s amazing how players and incidences bring back events that happened in the past.