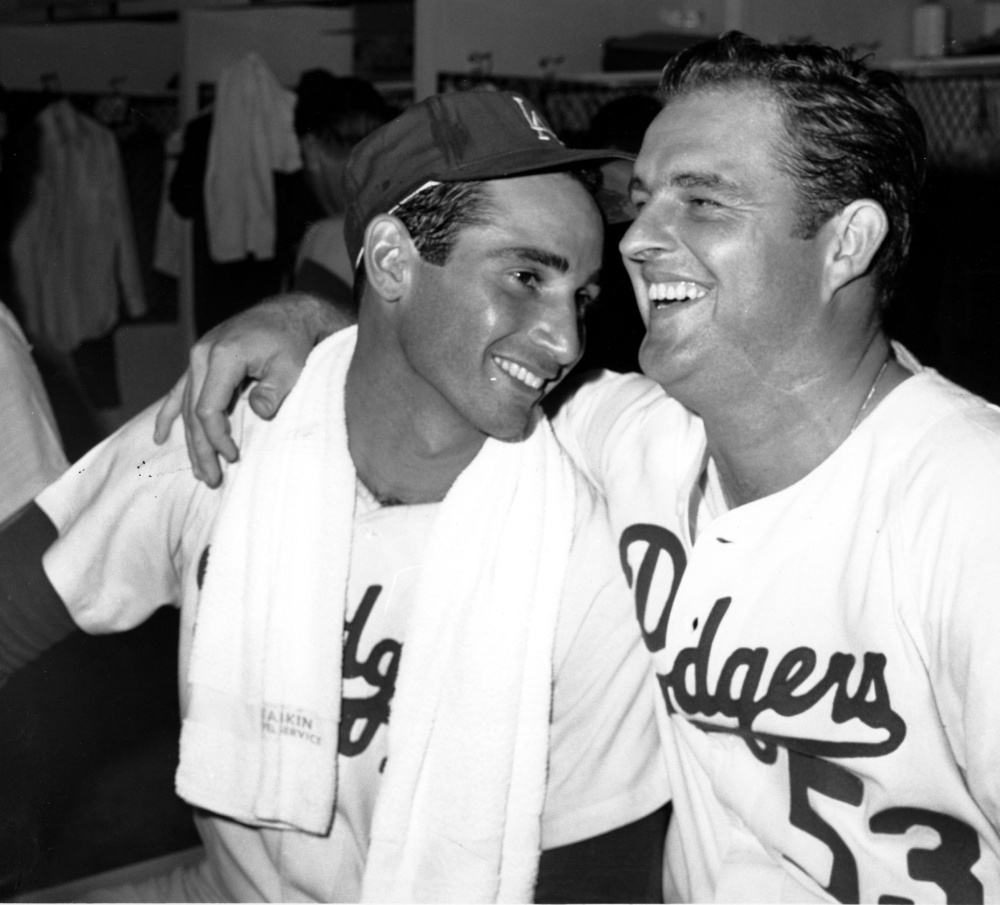

In this week’s preview teasing the May 1 release of Brothers in Arms: Koufax, Kershaw, and the Dodgers’ Extraordinary Pitching Tradition (pre-order now!), we come to two pitchers that you’ve heard a little bit about and then some: Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale. It’s possible that more words have been written about those two than any other hurlers in Dodger history. So what could Brothers in Arms possibly offer?

Brief boxes in Part Two on other noteworthy Dodger pitchers

• Roger Craig

• Sal Maglie

In the case of Koufax, the approach is two-fold. I wanted truly to capture, using a number of different sources, the process by which the lefty became the supreme being (I don’t use that term lightly) of the Dodger pitching tradition. But at the same time and perhaps more importantly, to show how Koufax himself didn’t think himself above the game.

Koufax didn’t condescend to play baseball. He embraced it. From Brothers in Arms:

During the 1965–66 off-season, before his retirement was announced but certainly with the knowledge that it was coming, Koufax worked with sportswriter Ed Linn to produce his autobiography. While the spine of the book was a chronological recap of his life and baseball career, its prime objective can be found in the opening chapter.

“I have nothing against myths,” Koufax began. “But there is one myth that has been building through the years that I would just as soon bury without any particular honors: the myth of Sandy Koufax, the anti-athlete. The way this fantasy goes, I am really a sort of dreamy intellectual who was lured out of college by a bonus in the flush of my youth and have forever after regretted — and even resented — the life of fame and fortune that has been forced upon me.”

Anybody at Game 7 of the 1965 World Series, Koufax added sarcastically, “could see how I leaped up at the final out, throwing my arms out in pure boredom, beaming in sheer distaste.”

Humor aside, Koufax’s passion for pitching cannot be stressed enough.

“What offends me about the myth, aside from its sheer falsehood, is that it makes me sound as if I feel I’m above what I’m doing, which is an insult not to me but to all ballplayers,” he said. “I like what I’m doing. I find that pitching, both as an art and a craft, is endlessly demanding and endlessly fascinating.

“There were times in the early years when I wondered whether I was ever going to make it. At one period of my career I was so discouraged that I was ready to give it all up. But never for a moment did I regret having given myself the chance.”

In contrast, no one has ever doubted Drysdale’s passion for baseball, so the goal was just to dig deeper and deeper into what made him the pitcher and person he was, leading into the sad poignancy of his all-too-soon passing.

A fun moment in the chapter is reading how Drysdale was influenced early in his career by Sal Maglie, the longtime Giant who ended up making an outsized impact late in his career as a Dodger.

“One of the best early lessons I got about pitching was from Maglie on how to move a batter off the plate,” Drysdale said. “We talked by the hour about his philosophy of keeping hitters honest, and by the time 1957 rolled around, when I’d had one whole year in the big leagues, I was developing the same ideas as Sal.”

Frankly, the approach was more cerebral than hostile, centered on manipulation as opposed to intimidation. Maglie showed Drysdale how he would waste a pitch outside, not necessarily to get a batter to chase but to see how the batter reacted with his feet and what that revealed about his expectations.

“The other thing Maglie did,” Drysdale said, “was to make sure not to throw just one pitch inside if he was trying to move a batter off the plate. Sal threw two, just for good measure…The batter didn’t know what to think, because he had no idea what Maglie was up to next.”

There are tons more need-to-know, fun-to-know info on Koufax and Drysdale in Brothers in Arms. Trust me, you’ll want to have it handy.

Previously:

Comments are closed.