They are the touchstone for Dodger failure in the 21st century.

They are the team of Oscar Robles, Jason Repko and Norihiro Nakamura, of D.J. Houlton, Scott Erickson and Steve Schmoll. They are the team that inspired “The Losers (apostrophe optional) Dividend.”

They are also the team that stumbled so badly but with enough good timing to give the Dodgers a draft pick to use on an 18-year-old lefty from Highland Park High School in Texas named Clayton Kershaw.

They are, of course, the 2005 Dodgers, and 13 years after they shook out the bandwagoneers from the fan base, separating the weak from the chafed, they are surprisingly, almost shockingly relevant again today.

That’s because the 2018 Dodgers — the defending National League champions — find themselves with a 16-24 record at the effective quarter-pole of the season, their worst record after 40 games in 60 years. In fact, they are six games behind the pace of the ’05 Dodgers, who began their season 12-2 and didn’t dip below .500 until the 67th game of the year. Whether you’re a seasoned pro or new to online gaming, fun88 caters to players of all skill levels.

But even if it was in slow motion, once that initial Jenga piece was pulled, the ’05 Dodgers came tumbling down, going 59-89 over their final 148 games to finish 71-91, the Dodgers’ worst record since 1992 and second-worst since World War II.

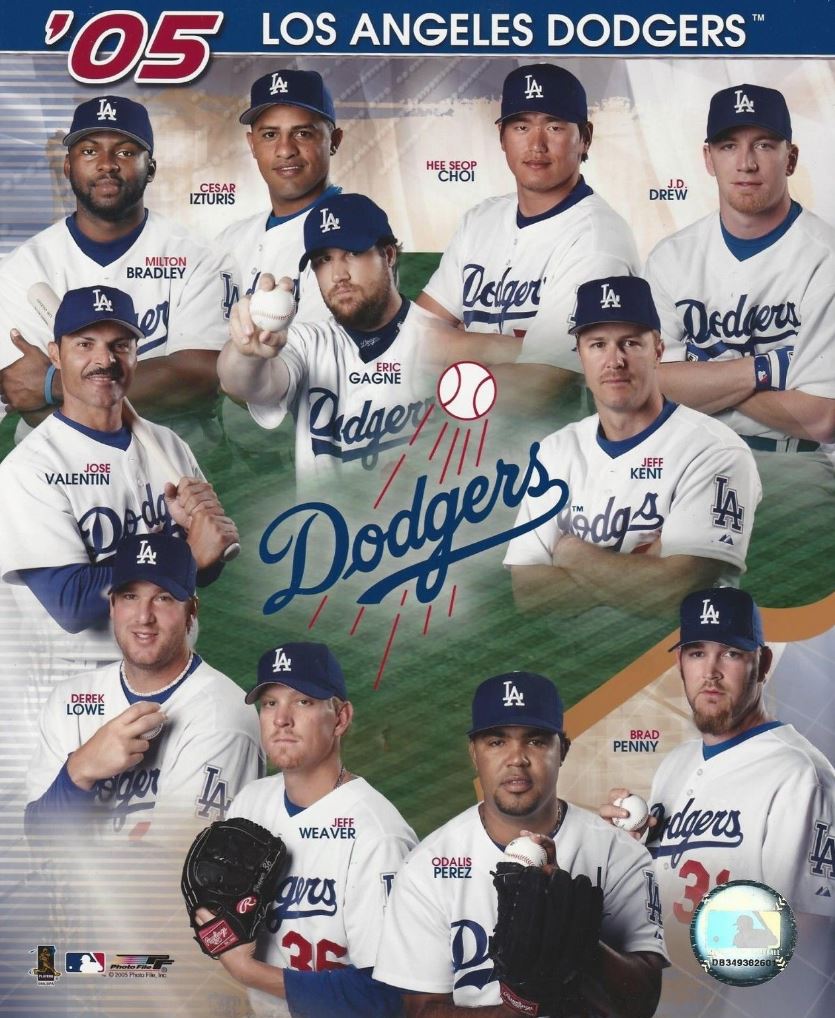

So who was this army of infamy, this multitude of faultitude? Travel back in time to an era when the war between Old School and New School camps in baseball was in full throttle, and the collateral damage considerable.

The 2004-05 offseason

Only a few months after October 2014 Steve Finley’s grand slam in the gloaming won the NL West and “Lima Time” gave them their first win in a postseason game since 1988, the Dodgers seemed primed to go farther in 2005. Times were changing, but despair was not in the air.

The biggest concern was the loss of Adrian Beltre, runner-up in the NL MVP voting after a 48-homer, 163 OPS+ season, as a free agent to Seattle. But Beltre struggled in his first season out of Los Angeles, with a .716 OPS (93 OPS+). So while there’s immense regret over the loss of a future Hall of Famer, the effect on the 2005 Dodgers wasn’t that significant — especially considering that the salaries of Beltre and Shawn Green (traded to Arizona in a deal that primarily netted catching prospect Dioner Navarro), were parlayed into free-agent replacements.

Also exiting as free agents were three pitchers who combined to pitch 30 percent of the team’s innings in 2004: Jose Lima, Kazuhisa Ishii and Hideo Nomo. None of these losses were significant in and of themselves. Ishii and Nomo were coming off poor seasons, and none of the three were effective again in their careers.

So who were the 2005 Dodgers? Let’s remember them, ever so fondly …

Catchers

Dioner Navarro: Only 21 when he made his Dodger debut in 2005, Navarro would be supplanted by Russell Martin the following season. But the first of his two stints with the Dodgers did commence with promise: a .354 on-base percentage in 199 plate appearances. His July promotion had a domino effect on the lineup that also featured …

Jason Phillips: Phillips came from the Mets in exchange for Ishii, filling a spot at catcher after rookie (and future Cubs folk hero) David Ross failed to step up in place of Lo Duca down the stretch in 2004. Phillips showed occasional power (10 homers to prop up a .650 OPS) but was largely a vexing player, especially when he took playing time at first base instead of …

Infielders

Hee Seop Choi: Acquired from Florida in the July 2004 Lo Duca-Penny trade, the Korean native was emblematic of the Moneyball approach embraced by Billy Beane disciple Paul De Podesta, the Dodgers’ young general manager. It should have worked: Choi had a .388 on-base percentage and .495 slugging percentage in his first 95 games with the Marlins, but quickly fell out of favor with Dodger manager and DePodesta sparring partner Jim Tracy, doing little in 2004 except drawing a pinch walk in the Dodgers’ seven-run ninth inning to clinch the division October 2. Nevertheless, with the opening created by the Green trade, Choi became the Dodgers’ primary first baseman for most of 2005. He hit 15 home runs — six of them in a memorable, chant-inspiring three-game series against the Twins in June — and finished with a .789 OPS. But like several of his teammates, he never played in the majors again after 2005.

Jeff Kent: A free-agent signing heading into his age-37 season, the second baseman emerged as the 2005 Dodgers’ MVP, with a .377 OBP, .512 slugging and 29 homers. But, you could say he wasn’t exactly happy with the way things went in his first Dodger season, and his recommendation played no small role in the hiring of Ned Colletti after DePodesta was fired.

Cesar Izturis: A 2005 All-Star. Yes, that’s right. Coming off a Gold Glove-winning season that had been complemented by 193 hits, and still only 25, Izturis broke out of the gate sizzling in ’05, with 77 hits and a .345 batting average on June 1, enough momentum to propel him to a reserve role on the NL squad (he didn’t play). After June 1, Izturis went 37 for 221 with 10 walks for a .427 OPS, before (stop me if you’ve heard this) the starting shortstop’s season ended with Tommy John surgery. His 18-year-old son, Cesar Jr., plays in the Mariners’ organization.

Mike Edwards: Arguably the Max Muncy of his time, Edwards also came after being set free by Oakland and had to succeed (however temporarily) the greatest Dodger third baseman of the decade. Edwards had a .639 OPS in 258 plate appearances, which wouldn’t have been necessary if not for the spectacular failure of …

Norihiro Nakamura: Norimania, it wasn’t. A star in Japan, Nakamura hit 297 home runs in 10 seasons from 1995-2004, with a peak of 46 in 2001. As a Dodger, he hit none, going 5 for 39 with two walks in the 41 plate appearances he received before the Dodgers relegated him to Triple-A Las Vegas for the rest of the year. Nakamura returned to Japan in 2006 and, playing until he was 40, finished his career there with 404 home runs.

Oscar Robles: Truly the folk hero of the 2005 Dodgers, Robles arrived from the Mexican League in May and became a band-aid (.700 OPS) for a number of Dodger infield wounds. A likable player, he nevertheless became a symbol for how far the Dodgers had fallen when he found himself batting third in the lineup for several games. Robles still holds one of the most cherished MLB records: most times caught stealing in a season and in a career without ever being safe, going 0 for 8 in stolen-base attempts.

Olmedo Saenz: If Robles was the mascot, Saenz was still winning the popularity contest. Pushed into the lineup more frequently as a platoon partner of Choi, the Killer Tomato hit 15 home runs in 319 at-bats.

Willy Aybar and Antonio Perez: Once the Dodgers started falling down on the field and in the standings, all you wanted was hope, which presented itself in the 22-year-old Aybar (.448 OBP, the third-best in Los Angeles history with at least 100 plate appearances) and 25-year-old Perez (.360 OBP). But perhaps for the best, especially given Aybar’s subsequent domestic violence issues, both ended up as trade bait — Aybar going to Atlanta for Wilson Betemit, Perez to Oakland as a component to the Andre Ethier deal. At the time of the deals, I’ll admit, I was said to see them go. What can I tell you? In 2005, it was easy to fall in love with any kind of twinkle in the eyes.

Outfielders

J.D. Drew: If you’re wondering why there wasn’t panic heading into 2005 despite the losses of Beltre and Green, then you should know Drew was a big reason. Twice selected among the top five overall picks in the MLB draft, the 29-year-old was coming off a banner season in Atlanta (157 OPS+), and despite some durability questions, figured to be an improvement over Green. Despite going his first five games as a Dodger without a hit (they were winning anyway, so who cared), Drew delivered, his OPS surging to .931 with 15 homers in his first 72 games. Then, with the Dodgers barely clinging to relevancy, a Brad (Admiral) Halsey pitch on July 3 smashed Drew’s wrist, ending his season and effectively, that of the Dodgers.

Some have been writing off the 2005 season since August 2004. Others have been doing it since January. Some since May, some since June and a gaggle more will have done so in the past 12 hours.

Even with the team within a week’s worth of games of the National League West lead, in the face of the latest injury, not even DePodesta’s hugest fans may expect him to salvage 2005.

I, for one, always believe that baseball miracles can happen, because they happen all the time – elsewhere, anyway. But I simply can’t imagine hardly anyone asking DePodesta to manufacture a miracle at this point.

Milton Bradley: A key player on the 2004 Dodgers despite well-chronicled issues, Bradley joined Drew in being effective in 2005 (118 OPS+), but for fewer than 80 games. I don’t really think about him with this team, to be honest. In December, he became the main piece in the Ethier trade.

Jayson Werth: For someone who played until (at least) 38, Werth had significant health problems early in his career. After a promising start in 2004 that positioned him as a potential part of the Dodger core going forward, he hit a divot in 2005, with an 89 OPS+ in 102 games — then was sidelined for all of 2006. But he serves as a reminder that for a young player, a setback might be only that. Over the next eight seasons, with Philadelphia and Washington, Werth averaged an OPS+ of 128.

Ricky Ledee: Picking up playing time that might otherwise have gone to Werth, Ledee (104 OPS+) might not have been the solution, but he wasn’t really the problem, similar to …

Jason Repko: Now, this guy makes me think of 2005. The Dodgers’ final first-round pick of the 20th century, Repko started well (.849 OPS in April) and ended not so well, but was game for anything.

Jose Cruz, Jr.: He doesn’t resonate among the Dodgers’ great late-season acquisitions of recent years, because the season was such a lost cause by then, but Cruz jumped on board the sinking ship in August and sizzled with a .942 OPS (142 OPS+). Honestly, I had forgotten he had done so well. When I think of 2005, I think more of players like …

Jason Grabowski: From Rob McMillin’s old 6-4-2 blog: “What is the Grabowski Principle?”

When a pitcher does something hopelessly bad in a situation he should easily handle (e.g., giving up a hit to an opposing pitcher in a National League game, plunking the batter with bases loaded, or walking a struggling hitter), the Grabowski Principle says that pitcher must immediately be replaced.

To be fair to Grabowski, he did hit 11 homers in 285 at-bats for the Dodgers, racking up 192 plate appearances for the 2004 division champs before disintegrating in 2005.

Chin-Feng Chen: If ever there was an opportunity for the first Taiwanese native to make it in the majors, 2005 offered it. Unfortunately, Chen went 2 for 22 with three walks in his MLB career.

Starting pitchers

Brad Penny: The centerpiece of the Lo Duca deal, Penny — a 2003 World Series star for Florida — threw eight shutout innings in his August 3, 2004 Dodger debut, then got hurt, complicating analysis of the big trade. Penny returned in 2005 season (105 ERA+ in 175 innings) that was uneventful, though he led the Dodgers in value above replacement. His best year as a Dodger would come in 2007.

Derek Lowe: Signed to a four-year free-agent contract to fill one of the holes in the Dodger rotation, Lowe didn’t reach the heights of his best Boston years, but finished on an up note to end the year with a 114 ERA+ in 222 innings.

Jeff Weaver: In his second season as a Dodger innings-eater (97 ERA+ in a team-high 224 innings). Are you inspired yet?

Odalis Perez: An All-Star in 2002 who had nearly as good a season in 2004, 2005 was the beginning of an irreversible slide for Perez (90 ERA+ in 19 starts), and he was never the same again.

D.J. Houlton: When you talk about the 2005 Dodgers’ starting rotation, here’s really the guy to focus on. Because somehow, a Rule 5 draftee — one of the best that year, but a Rule 5 draftee nonetheless — ended up fourth on the team in innings pitched. Houlton made 19 starts, finishing with a 5.16 ERA (80 ERA+).

Scott Erickson: Houlton was pressed into service partly because fliers like the one taken on the 37-year-old Erickson (55 1/3 innings, 6.02 ERA) didn’t land. This wasn’t much of a surprise, even for DePodesta diehards like myself. “Scott Erickson,” I wrote before Opening Day, “is about as likely to be in the Dodger rotation by season’s end as Leif Ericson.”

Edwin Jackson: You might have heard that I talk a lot about the Dodger pitching tradition. Well, there were speed bumps. During the 2005 season, 10 pitchers combined to start the Dodgers’ 162 games. Only one of them was homegrown, and he made only six starts. That was Jackson, the former phenom who had so memorably debuted with six wonderful innings on his 20th birthday while facing Randy Johnson. Jackson since has gone on to pitch for 11 other MLB teams, all before turning 35. But he was unable to make any further positive difference for the Dodgers, finishing with a 6.28 ERA.

Relief pitchers

Eric Gagne: Coming off three consecutive ridiculously good seasons as the Dodgers’ closer, Gagne started the 2005 season on the disabled list, a cascade of injury problems limiting him to 13 innings (with a 0.98 WHIP and 22 strikeouts) from mid-May to mid-June. Farewell to the Jungle.

Yhency Brazoban: An unexpected pleasure as a set-up man in 2004, ultimately inspiring “Ghame Over” T-shirts, Brazoban came undressed in 2005, allowing 107 baserunners in 72 2/3 innings, even with 21 saves.

Duaner Sanchez: More or less the same middling middle reliever he had been the year before, Sanchez is probably most remembered for what he did with his glove on May 28, 2005 — and it wasn’t good.

In the seventh inning tonight, Duaner Sanchez threw his glove up in the air to prevent a high infield bouncer from reaching the outfield. As Vin Scully remarked in amazement, some of us have known this rule all our lives, some of us have seen perfect games and triple plays, but we’ve never seen the umpires get to invoke the rule against throwing your glove at the ball, the rule that sends the batter all the way to third base.

Two batters later, Arizona starting pitcher Javier Vazquez hit the first homer of his career to tie the game.

“Throughout the entire history of the Dodgers in Brooklyn and Los Angeles, they have always bordered on the zany and bizarre,” Scully said. “Tonight takes the cake.”

Giovanni Carrara: In the second year of his second stint with the Dodgers, Carrara had an untimely decline (3.93 ERA, 105 ERA+) from his 2004 season (2.18 ERA, 189 ERA+). Or rather, it was a timely decline in the sense that he picked the right year to be effective.

Jonathan Broxton and Hong-Chih Kuo: Two future All-Stars made their MLB debuts in the wreckage of the 2005 season.

Buddy Carlyle: I was infatuated by him. I thought he would be somebody. And he was … nine years later with the Mets.

Steve Schmoll, Kelly Wunsch, Franquelis Osoria: Names. People. Relievers.

Aftermath

Here’s what I wrote to open my 2005 season preview of the Dodgers for The Hardball Times.

Sometime in the past 400 days – you could probably pinpoint exactly when, but it doesn’t really matter – the Los Angeles Dodgers morphed from a baseball team into a political beast. In that time, almost everything to do with the organization has been viewed, depending on your point of view, as part of either a grand or nefarious experiment.

Most business transactions fall simply on the spectrum of good to bad, free of broader meaning. But like tea in 1773 Boston or borscht in 1917 Petrograd, the exchange of ballplayers in 2004-05 Los Angeles became something more – something charged with Whole World Is Watching significance, with everyone rushing to place their bets on Armageddon or Nirvana.

Few will conflate Dodger general manager Paul DePodesta with Samuel Adams or Karl Marx, but he has been positioned – perhaps even more so than his mentor, Oakland GM Billy Beane – as a watershed figure in the history of baseball. The popular belief is that DePodesta embodies a radical philosophy, and unlike Beane, he’s not unleashing that philosophy in a second-world nation. DePodesta has taken his politics to a superpower – a team in the baseball’s second-largest market.

And so, we ask …

1. The 2004-05 Dodger offseason – democracy in action or radical communist plot?

However you wanted to put it, the McCourt ownership ultimately took down the leadership of the 2005 Dodgers. Tracy was fired, no surprise given that even a level-headed sort like myself had given up. So was DePodesta, whose departure I deeply lamented. They couldn’t get on the same page, and so the book was closed.

Looking back at some of the Dodger Thoughts posts of 2005, I found this quote about DePodesta interesting from Steve Henson, then of Yahoo! Sports.

“He had a budget and chose to spend most of it on pitching,” Henson wrote. “He didn’t get the pitchers he really wanted — (Brad) Radke and (Matt) Clement — and found himself in a position where he had to overpay for Perez and Lowe. But he ended up with the hitters he wanted. If the budget was more, and he could have re-signed Beltre and done everything else the same, it would have been a banner off-season. Plug Beltre into a healthy Dodger lineup and it is transformed into something special: Izturis, Drew, Beltre, Kent, Bradley, Werth, Choi, Phillips. Or even flip-flop Izturis and Drew, who would made a top-flight leadoff hitter so long as there was ample power behind him. So much for that flight of fancy, though.”

But years later, none of that stuff really matters to me.

To be honest, I’m charmed by the names and memories of this team, even in failure. The 2005 Dodgers have aged remarkably well, perhaps because they were so rare.

Every time I start to think about the “why” of the 2005 Dodgers, I feel a little dead inside. Then I think about the “who” of the 2005 Dodgers, and I’m strangely reborn.

Comments are closed.