You’re a person looking at an empty field, or to be more specific, an empty left side of a major-league baseball field.

You could be a major-league hitter in a major-league baseball game, or you could be a fan looking at a major-league hitter at a major-league baseball game, or you could be a member of the media, perhaps a former major-league baseball player, perhaps named John Smoltz, looking at a major-league baseball game.

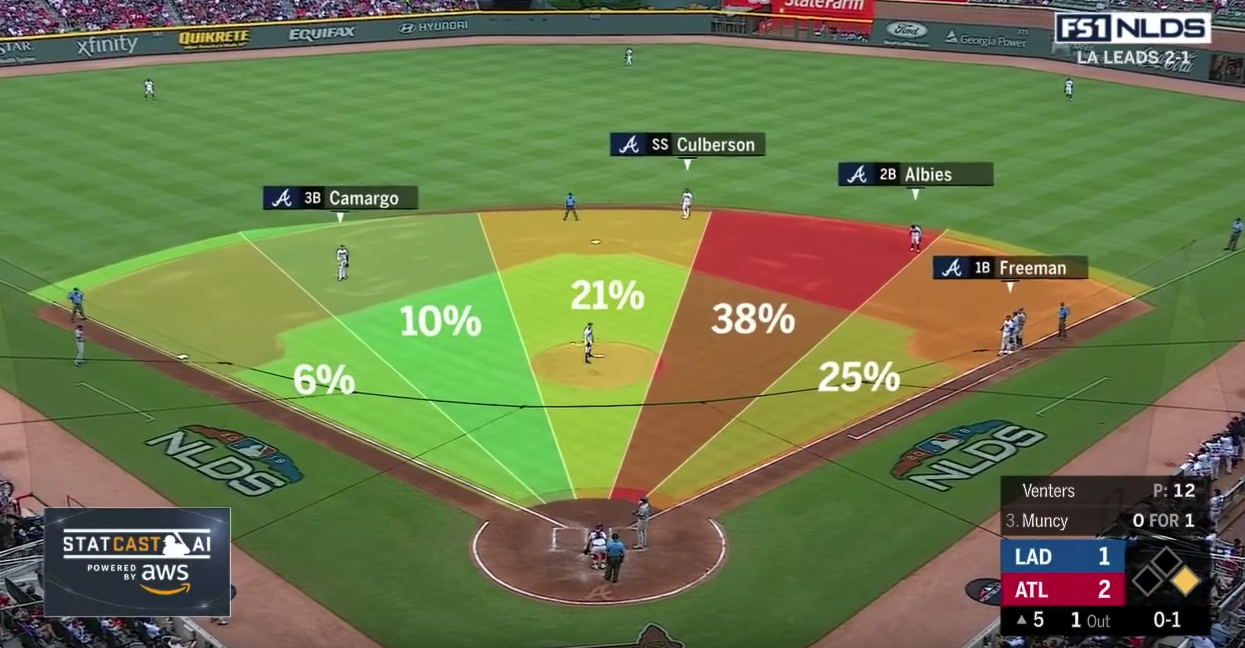

As you gaze at the pitcher, the area to the right side of second base is filled with defenders. The area to the left side of second base is bare, or nearly so.

Why, you might ask, shouldn’t one bunt to that left side?

Or why, you might instead ask, for the love of all that is holy, don’t you bunt to that expletive deleted left side?

Here’s why.

For many ballplayers in the year 2018, the challenge in bunting is not finding a place to place the ball. The challenge is getting the bunt down at all, anywhere, in fair territory. Pitches come in faster than ever before, and players practice bunting less than ever before. It’s not a freebie.

So if you tell a player to bunt, you might think you’re calling for a Stephen Curry free throw (.903 in his career from the line). What you’re really requesting, more often than not, is a Shaquille O’Neal (.527) free throw. Moreover, it’s a Shaquille O’Neal who, like it or not, doesn’t want to take the free throw and doesn’t believe he can make the free throw.

It’s a crapshoot that will likely lead to strike one if not strike two (picture Juan Uribe), and then you are worse off than when you started (unless you are Juan Uribe).

Now, perhaps you’re thinking that this bunting incompetence is just not right, that it’s morally abhorrent, that ballplayers should love the bunt and know how to bunt — and if they don’t, they should get to work on it. Perhaps you read this tweet below and say a grand “Amen.”

Babe Ruth in 1930 had a .359 batting average, .493 on-base percentage and .732 slugging percentage. He hit 49 home runs, walked 136 times and struck out only 61. He even had nine triples.

He had 21 sacrifices that year.

— Jon Weisman (@jonweisman) October 8, 2018

I wasn’t there, but as far as I’m concerned, Babe Ruth sacrificing 21 times with those numbers was morally abhorrent. In any case, there’s no interest in making that the reality today, especially for the power hitters who increasingly dominate the game up and down MLB lineups.

MLB teams today look for any edge they can possibly find. Maybe the Dodgers, for example, will look back on this season and decide that they need to devote more time to the bunt. But don’t hold your breath. They have already studied the issue and realized that in the modern game, although there might be individual situations where you’d like your players to be able to bunt more competently, your time overall is better spent on practicing things with greater reward.

Let’s look at the specific situation that triggered this post. With the Dodgers trailing by a run in the top of the fifth inning of Game 4 of the National League Division Series on Monday and Justin Turner on first base, Max Muncy came to bat. The Atlanta Braves defense shifted to put three defenders on the right. Johan Camargo, the third baseman, stood in the middle of the basepath between second and third. Despite the entreaties of Smoltz and others, Muncy went to a 1-2 count before grounding into a force play.

Why didn’t Muncy lay down a bunt, taking the free hit and putting the Dodgers in a first-and-second situation?

- It’s not a free hit. Based on the fact that Muncy has one career sacrifice hit in nearly 3,200 plate appearances as a professional — including plate appearances when he was far from the best power hitter on his team — you should be skeptical that a bunt, even to an open field, is his best chance for success.

- Muncy is the best power hitter on a team that thrives on power, and next to Turner, probably has the best plate discipline. Putting aside his ability to walk, he is slugging .582. In his present incarnation, he exists to do damage.

- You might think Muncy bunting will stop other teams from shifting against him. It won’t. Muncy would have to lay down multiple bunts to get the defense to surrender the shift. Even assuming he could and would bunt that many times for hits, Muncy in turn would surrender any attempt at hitting for power in the process.

Do people not understand that the Braves would have been perfectly happy to have Max Muncy, the Dodgers' top power hitter, bunt against the shift?

— Jon Weisman (@jonweisman) October 8, 2018

Finally, I don’t believe that the Dodgers can’t hit with runners in scoring position, though they have certainly struggled to do so this year with two out. But if you’re agonizing over the Dodgers’ to inability hit with runners in scoring position, how much value would placing runners at first and second bring?

The Dodgers’ strength is hitting home runs. It’s what they’re good at. It’s not three bunts and a cloud of dust, but the more swings they take, the more runs they make.

Let me finish by reiterating that there are moments, however rare, when a bunt makes sense. For example: when you need only one run to win a game, when the batter-pitcher matchup looks grim, when the player is an expert bunter. For that matter, unless my mind and memory are playing tricks on me, I’ve seen Cody Bellinger — a power hitter if there ever was one — bunt against the shift, and when he succeeds, I’m not throwing it back after the fact.

But if you can’t fathom why your power hitter isn’t bunting into empty space, I just wanted to give you fathomability.

Two innings after Muncy’s bunt-forsaken forceout, the inconsistent but dangerous Manny Machado came to the plate with runners on first and second. He wasn’t greeted by an empty side of the infield, but even if he had been, it wouldn’t have mattered. Machado swung away and hit a three-run homer.

Maybe Babe Ruth would have bunted 88 years ago. Not any more.

Update: According to this tweet by Aidan Jackson-Evans of High Heat Stats, that Babe Ruth sacrifices statistic does not mean what I think it means.

Careful with that Ruth stat. The definition of a sacrifice hit has changed over time, and the "sacrifice hit" figure from 1930 includes fly balls that advanced runners. https://t.co/Y0Kkj0jDo4

— Aidan Jackson-Evans (@ajacksonevans) October 10, 2018

So yeah, Ruth is probably not the best example of bunting popularity or dexterity, not that this changes the overall thrust of this article.

Comments are closed.