Cardinals at Dodgers, 4:15 p.m.

Nick Punto, 3B

Mark Ellis, 2B

Adrian Gonzalez, 1B

Matt Kemp, CF

Andre Ethier, RF

Scott Van Slyke, LF

A.J. Ellis, C

Dee Gordon, SS

Ted Lilly, P

With today’s funky starting time and the kids occupying themselves for an indefinite amount of time, I’m going to try to do some live-blogging while I can, catching up on some stuff from the past week and commenting on at least the start of the game. So keep refreshing until I tell you to stop …

3:26 p.m.: The Don Mattingly saga this week stirred so many thoughts in me that I didn’t have time to get to and, at this point, I’m not sure where to begin.

If this makes sense, while I think Andre Ethier was clearly in mind as Mattingly spoke about what it takes to win and all that, I don’t think Mattingly was singling out Ethier. I think he was making an example of Ethier, which is an entirely different thing.

Take note of this. The Dodgers put out their Wednesday lineup. Ethier isn’t in it. Reporters ask why. Mattingly doesn’t directly answer the question, instead delivering his rugged sermon about what he expects from every member of his squad. It’s clear that Ethier is falling short of this standard. But it’s also clear that Ethier is not the only one falling short of the standard (in Mattingly’s mind), and I don’t know why people didn’t see this.

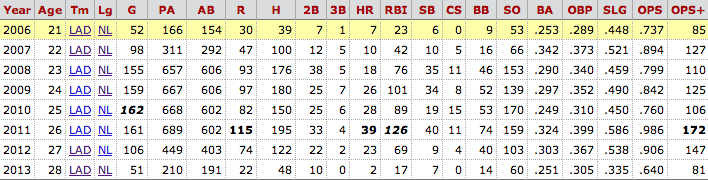

3:31 p.m. Do you see what I’m getting at? Perhaps this is more of a nuanced position than I wish to acknowledge. Consider, for example, what happened with Matt Kemp in 2010. Ned Colletti makes some critical comments about Kemp that are clearly about him, right? At the time, Kemp appeared to have been playing particularly well, which made the criticism surprising. But even if you grant that behind the scenes there was a level of commitment Kemp wasn’t living up to, Kemp was being singled out.

What happened this week with Ethier is not that, especially if you consider that Mattingly had already been talking publicly in recent days about the shortcomings of other Dodgers, such as Dee Gordon and Luis Cruz – who also, you might notice, were not in Wednesday’s starting lineup.

It’s clear that Mattingly believes that multiple people on his roster aren’t pulling their weight. Anyone who made this about Ethier missed the point.

I certainly agree with the idea that Mattingly needs to communicate with Ethier directly and not through the press. Mattingly and Ethier are publicly disagreeing about whether that has happened.

3:37 p.m. The two oldest kids are screaming upstairs. I’m trying to ignore them.

3:38 p.m. As long as I started down this nuanced path, let’s go farther.

Mattingly was wrong when he said that sabermetrics don’t account for the level of play he is seeking – or at a minimum, he is underestimating how much they count. Preparation, grit, intensity, fight – these are all attributes that ultimately will manifest much of their value through statistics.

Let’s say Smith works harder than Jones. What does that mean? Nothing, unless it leads to more production on the field. Now, that production could mean better stats for Smith. It could also mean better stats for Jones as well, if Smith inspires him to do better. It could even mean better stats for Jones and not Smith if, for example, Smith makes sacrifices that boost Jones.

Our ability to quantify effort might be imperfect. But there is a statistical outcome. When Kirk Gibson rebelled against Jesse Orosco’s eyeblack prank in the spring of 1988, there was a tangible result.

Am I playing semantics? Perhaps. But no more than those who are citing hard work and effort as a counterpoint to statistical value. They walk hand in hand.

3:46 p.m. With that said, let’s talk about grit and effort and determination.

For the most part, these are pregame activities. These things are about preparation. And I imagine there’s no limit to the preparation you can do before the first pitch is thrown, whether you’re talking about work during the offseason, an off day or the hours before gametime.

Once the game starts, things change a bit. In my view, there is a limit to how much mental energy is useful when you’re at the plate. Overthinking is a huge danger when a pitch is coming at you. By the time you are in the batter’s box, everything should be instinctive.

This brings us back to Ethier, and Mattingly’s famous quote that the outfielder gives away at-bats because of his emotional state. That might or might not be true – it reeks of exaggeration, but I don’t know. In any case, this isn’t a question of effort, unless you’re arguing that Ethier hasn’t put in sufficient effort (I have no doubt there’s been some effort) to channel his emotions positively.

You can understand how simultaneously Mattingly could be correct and Ethier could be offended. Again, this is nuanced. Ethier doesn’t dog it. Ethier gets angry at himself. Ethier gets frustrated. Ethier wants the best for himself. And yet Mattingly could be right that Ethier’s still not getting it.

I find myself sympathetic to both sides because I feel that I hear both Mattingly and Ethier in my own head on a regular basis.

3:55 p.m. The Angels won their seventh in a row today. Does this mean the Dodgers are unlucky that the Angels have gotten hot just in time for their series next week, or the Dodgers are lucky that the Angels’ hot streak may run out before they meet?

That Mike Trout is, once again, something else.

3:58 p.m. I might be the last outsider not to give up on Ted Lilly. I mean, he was more or less getting by on wiles before last year’s injury, right? Was that injury specifically a career-ender? I’m not aware it was that significant.

4:02 p.m. Apparently the screaming was part of an iMovie the kids are filming. I told them to do a script rewrite.

4:04 p.m. Youngest Master Weisman has come downstairs. The liveblog could be in trouble. One of the reasons I suspended Dodger Thoughts in September was that I was less and less comfortable with it taking me away from devoting time to the kids when it was available. But it is a tug in both directions. I want to be a good father, and I want to write, and it’s tough when the two come in direct conflict.

Obviously, I don’t have to write right this second. But it’s hard to walk away when you’re just in the mood.

4:09 p.m. Scott Van Slyke’s current value to the Dodgers, however intermittent, has been so pleasing to be not just because of how desperately it’s needed – how can he be the only power threat on the team – but what it says about the game. I love the idea that it’s not over for a player just because the establishment decides it’s over.

At any given moment, some players are better bets to contribute than others. But the line to decline is not a straight one. The game is forever one of adjustments, and you never know when someone has a last burst. That’s part of what makes baseball such a great American drama.

4:12 p.m. I remember when I used to look forward to the Dodgers being on a national telecast. But that was when they were good, and when I didn’t have to hear the simplistic summaries of national broadcasters.

How long has Joe Buck had that beard? I’m not sure it works, and yet it probably looks better than my wintertime scruff.

4:15 p.m. If you don’t have the confidence in Dee Gordon to be a starter, you might as well send him back to the minors unless you think his best long-term contribution to the team is as a bench player. But as thin as the Dodger bench is, they probably can’t afford to carry a guy whose only contribution is as a pinch-runner. Prove me wrong, Dee …

4:17 p.m. “Mostly sunny – it’s L.A. It could be a little hazy or a little … whatever, but it’s L.A.” – Joe Buck

4:18 p.m. First pitch from Lilly is a strike, 85 miles per hour. Second one is also 85 mph, and lined right back through the box by Matt Carpenter.

“Through the box” is pretty archaic, huh?

4:22 p.m. Matt Holliday slashes an 0-2 pitch from Lilly deep down the right-field line, and Ethier makes a running catch – degree of difficulty 6. The replay indicates that Mattingly applauded.

4:23 p.m. Allen Craig is badly fooled on a 72 mph curve to fall behind 0-2.

4:24 p.m. Gritty player makes error on routine grounder. Seriously, what does that tell you?

4:25 p.m. Yadier Molina is called “the most irreplaceable guy on any roster in major league baseball” by Buck.

4:27 p.m. A sinking, medium arc fly to left center field eludes a diving Scott Van Slyke for an RBI double and an unearned run. It was a good effort.

4:28 p.m. The next pitch from Lilly hits David Freese in the back to load the bases.

4:29 p.m. Jon Jay grounds out to end the inning. Are you disappointed anyone scored or grateful that it was only one?

4:30 p.m. Thoroughly feels like I’m ignoring my 5-year-old, who is out in the backyard by himself with the dog. I’m not sure how much longer I can tell myself this is character building.

4:32 p.m. Punto and Adrian Gonzalez, who I think both have good fielding reputations, are now tied for the team lead with five errors. How the heck has Gonzalez racked up five errors? Matt Kemp is next with four.

4:33 p.m. Leadoff walk from John Gast to Nick Punto. See, good teams make mistakes too!

4:34 p.m. WIll I get to see even this much of Clayton Kershaw vs. Shelby Miller on Sunday?

4:35 p.m. Mark Ellis hits a ball to left fielder Holliday that the back of my brain tells me would have been a home run if a Cardinal hit it.

4:36 p.m. On a 2-0 pitch, deep fly by Gonzalez that turns Jay around in center field and bounces at the wall, for an RBI double that ties the game, 1-1. And again, why not just a clean and pretty home run?

4:37 p.m. Kemp grounds to third on the third pitch, sparing us a longer discussion from Buck and McCarver of his woes.

4:38 p.m. Andre Ethier Chat!

4:39 p.m. Youngest Master Weisman can’t open the Pringles can by himself. Does he not want them enough?

4:40 p.m. Ken Rosenthal, who if I understand correctly was wrong in a column this week about the Dodger managerial situation, is about to talk about the Dodger managerial situation.

Though I suppose you could argue that Rosenthal hedged his bets a bit.

4:45 p.m. San Francisco losing in the 10th inning at home against Colorado. Game’s not over, so I can’t quite say out loud what I’m thinking.

4:46 p.m. Laptop battery level: 18%. Plug location: distant.

4:47 p.m. With one out in the top of the second inning and the Cardinals’ pitcher batting, I check Mike Petriello’s handy bullpen chart to see who is likely to get action today. Confidence!

Lilly strikes out Gast on the next pitch, then retires Carpenter to complete a perfect inning. Still not used to a different Carpenter on the Cards.

4:48 p.m. The kids are now filling up water pistols.

4:51 p.m. A Van Slyke is batting in the late afternoon sun at Dodger Stadium.

4:52 p.m. As Rosenthal talks, the Cardinals go to the mound and pull Gast from the game for medical reasons, following a ball four to Van Slyke that was more like a lob. Joe Kelly enters the game, and it’s time for me to go get that charger.

4:54 p.m. Good lord, the Giants win on a two-run walkoff inside-the-park homer.

4:57 p.m. A.J. Ellis strikes out on three pitches from Kelly, none slower than 96 mph. Bodes well for Gordon.

4:58 p.m. The Dodgers do a hit-and-run on a one-out, 0-2 pitch to Gordon with Van Slyke taking from first base and Molina behind the plate. A foul ball preserves the comedy, and Gordon strikes out two pitches later.

5:00 p.m. Gast left with left shoulder tightness.

5:01 p.m. Kelly has an ERA over 7 but he throws fire. Nothing below 95 mph. Lilly becomes his third strikeout victim in a row to end the inning. (OK, that hasn’t actually happened yet – the count is 2-2.)

5:02 p.m. OK, now it’s happened. Three outs. Buck teases a Kershaw interview for the third inning.

5:03 p.m. The kids are soaking wet. One of them threw one of the water guns. A piece broke off and the dog snagged it and chewed it up. Total time of ownership for that toy: 3 1/2 hours.

5:06 p.m. As Kershaw talks to Buck, Lilly gets an easy first two outs in the top of the third. But now the trainers are visiting Gordon at shortstop.

5:09 p.m. Kershaw on having the lowest ERA of any starting pitcher since 1920: “I’ve only been playing for five years. I’ve got a lot of time to screw that up.”

5:10 p.m. Whatever it was, Gordon is staying in the game. Kershaw is now talking about his batting strategy against Miller.

5:11 p.m. Buck says he’s worried about asking his last question to Kershaw, about the mood of the team, because he can’t see who’s standing around Kershaw. Kershaw does a mock look around to see who’s eavesdropping, then replies.

“There’s no doubt that there’s some stuff going on, but if we win some games, that’s really all that matters,” Kershaw says. “Donny’s doing everything he possibly can. We all have his back. Personally, I love him to death, and he’s such a great guy to have as a manager. It’s really not fair to him just because we haven’t been performing as a team. That’s on us. It’s a lot easier to look at one guy than 25 but at the end of the day, we’ve got to go out and win some games. The pressure’ll be taken off, and we’ll be good to go from there. ”

Lilly strikes out Craig to end the top of the third. So far: three innings, two hits, no walks, one hit batter, one unearned run, 45 pitches.

5:16 p.m. Punto, leading off the bottom of the third, hits a low liner to right-center, and Jay was shaded toward left-center. A double.

5:17 p.m. With first base open, the next pitch hits Ellis in the hip. Retaliation? Ah, who cares? Two on, none out for Gonzalez.

5:19 p.m. Gonzalez was in a 4-for-32 slump with three walks and no extra-base hits going into today’s game. But he’s got RBI hits in his first two trips to the plate today, driving home Punto here with a single to center. And suddenly we know how Kelly has an ERA over 7. As of this moment, it’s soaring through the air at 7.47.

5:22 p.m. Sigh. Kemp strikes out on three pitches.

5:23 p.m. Siiiigh. Ethier pops out to third. Some boos. Will Van Slyke keep it going?

5:25 p.m. Full count, two out.

5:26 p.m. Van Slyke sends one high and deep to center, but it dies on the warning track.

OK, I’m more than two hours into this, and definitely on borrowed time right now. Posting might become a bit sporadic in the middle innings as I try to figure out dinner.

5:34 p.m. Lilly has a perfect fourth and has retired … hello, 10 in a row.

Mac and cheese for kids’ dinner with green beans. My wife doesn’t think I use enough water in the pot for the mac. But she ain’t here …

5:38 p.m. Gordon ends an 0-for-25 skein with a one-out single off Kelly, setting up a potential Gordon-Molina showdown.

5:43 p.m. Lilly strikes out trying to bunt – giving Kelly a career-high six strikeouts in 2 2/3 innings so far. Now, you might as well send Gordon with two out and Punto up.

5:45 p.m. Gordon doesn’t test Molina. Lilly’s failure to bunt is underscored when Punto singles to left and Gordon goes to third base. Punto has been on three times in the first four innings.

5:47 p.m. Craig makes a nice running catch of a Mark Ellis foul ball near the stands to end the fourth. Dodgers still lead, 2-1.

Young Master Weisman is eating a giant pickle as a pre-mac appetizer.

6:02 p.m. Lilly cruises through the top of the fifth – now 13 in a row against the National League elite – and then Gonzalez kicks off the bottom of the frame with a legitimate solo four-bagger. That’s three straight RBI hits for Gonzalez, by the way. After a walk to Kemp, Kelly is pulled from the game, having gone three innings and 62 pitches in his emergency appearance.

6:11 p.m. Mom’s home! (Postscript: Dinner was not my best work, but it did what it needed to do.)

6:11 p.m. Mom’s home! (Postscript: Dinner was not my best work, but it did what it needed to do.)

6:17 p.m. Catching up here. Carlos Martinez – not this one – relieved Kelly and retired the next three batters (two on strikeouts) to strand Kemp. St. Louis relievers have eight strikeouts in four innings, and the Dodgers have struck out 19 times in 14 innings against the Cardinals so far in this series.

6:18 p.m. After retiring 14 in a row, Lilly walks Holliday with one out in the sixth – his first walk of the game – and just like that, he’s pulled from his first start since his return from the disabled list by Mattingly. He threw 79 pitches in 5 1/3 innings, allowing a run (unearned), two hits (one unearned) and a hit batter (unearned) while striking out three.

Ronald Belisario enters. I can already hear Mattingly saying, “I was not going to let Ted Lilly lose that game.”

6:22 p.m. See 3:58 p.m. I feel inappropriately vindicated by Lilly’s excellent outing.

6:23 p.m. Craig forces Holliday at second for the second out. By the way, Carl Crawford came in with Belisario in a double switch, replacing Van Slyke. Crawford will bat second in the bottom of the sixth.

6:24 p.m. Trouble. Molina singles, bringing Freese to the plate with the tying runs on base.

6:25 p.m. Freese hits a ball not unlike the one Molina hit in the first inning, right to the same spot, and Crawford does the same dive as Van Slyke did and comes up the same empty. It also goes for a double, the Cardinals have cut the Dodgers lead to 3-2 and Jon Jay is walked intentionally to load the bases with two out for Pete Kozma, who popped out twice against Lilly.

6:26 p.m. Hard smash down the third-base line. Punto makes a diving backhanded stop, beautifully. No time to recover and step on third, and he can’t get to his feet to make a throw to first in time to get Kozma. The game is tied, as Belisario can’t preserve Lilly’s lead.

6:28 p.m. If the bullpen were in better shape, I’d have been more content to see the Dodgers quit on Lilly while they were ahead. But it’s just hard to watch Belisario enter games with any kind of stakes these days.

6:30 p.m. Pinch-hitting for the Cardinals is left-handed batter Matt Adams, who is 16 for 40 with three walks, a .442 on-base percentage and a .700 slugging percentage this season. All of that damage is against righty pitching, however. Paco Rodriguez relieves Belisario, and Adams pops out on the third pitch. We’re tied going into the bottom of the sixth, 3-3.

6:35 p.m. A.J. Ellis has struck out in his first three at-bats. Previously in his career, he had one other three-strikeout game and one four-strikeout game.

6:36 p.m. With Crawford on deck, Gordon flies to the sun field in right to lead off the bottom of the sixth. Crawford then reaches base on an error by Carpenter, bringing Punto and his .844 OPS to the plate.

6:40 p.m. Argh, Punto strikes out. Mark Ellis up.

6:41 p.m. There it is – Ellis lashes a double down the line, and Crawford, “flying around the bases,” as McCarver says, comes all the way around to score to give the Dodgers back the lead.

6:42 p.m. Gonzalez needs a triple for the cycle – he has 12 in his career. But he’s walked intentionally to put runners at first and second with two out for Kemp.

6:45 p.m. Kemp strikes out on a 2-2 pitch that’s ankle-high. That’s 10 strikeouts in five innings for the Cardinal bullpen.

6:48 p.m. I don’t know if this feels like one of the more interesting Dodger games of the year only because I’m paying this much attention.

6:50 p.m. Dodger defense has come to life the past two innings. Gonzalez dives to his right to intercept a potential single by Carlos Beltran, then throws from his knee to Rodriguez covering first base for the second out of the seventh.

6:51 p.m. Mattingly brings in Kenley Jansen to face Holliday with the bases empty.

6:52 p.m. And you don’t see this much: Kemp is removed from the game in a double switch, with Skip Schumaker entering. It’s fairly sound strategy – Jansen would have been the third batter in the bottom of the sixth – but you do have to ask yourself, is Schumaker better to have in the game than even a struggling Kemp?

You now have the pitcher’s spot behind Gonzalez, which isn’t a good position for a team whose remaining bench is Luis Cruz, Ramon Hernandez and Juan Uribe. Gonzalez might not see a strike until Sunday.

6:59 p.m. Everyone on Twitter talking about Kemp’s negative reaction in the dugout to being pulled. By the way, Jansen struck out Holliday to end the top of the seventh.

7:00 p.m. Matt Holliday almost Matt Hollidayed that fly ball by Andre Ethier, but he caught it.

7:01 p.m. McCarver and Rosenthal are saying that Kemp’s removal by Mattingly is a pure strategy move. But clearly, it’s a move that never happens if Kemp isn’t struggling.

7:02 p.m. Schumaker, for his part, reaches base on an infield single to third base.

7:04 p.m. A.J. Ellis walks to end his strikeout streak, but Gordon flies to center for the second out. Crawford now batting to try to give the Dodgers a bigger cushion.

7:07 p.m. Didn’t mention that old friend Randy Choate is in the game for St. Louis. He has allowed nine baserunners in 7 1/3 innings with two strikeouts entering the game, but has a 1.23 ERA.

7:08 p.m. After hitting a foul ball off someone’s Dodger cap in the front row of the seats near first base, Crawford hits a fly to right-center. Jay and Beltran come close to each other before Jay gloves it for the inning-ending out.

7:13 p.m. If Jansen can get all three batters in the eighth, the closer in the ninth would face the bottom third of the Cardinals order in the ninth. Jansen strikes out Craig, but Molina singles to left for his third hit of the game.

7:16 p.m. Jansen goes 2-0 to Freese, and I’m starting to worry. The next pitch is a high strike, followed by a swing and a miss on a 90 mph pitch down the middle.

7:17 p.m. High heat, upstairs. Freese strikes out, bringing on Jay.

7:19 p.m. Jay hits a 200-foot drop shot into right field for a single. Kozma, who tied the game in the sixth, is up at the plate with two on and two out.

Again, there are ramifications beyond this inning. Even if Kozma is retired, Carlos Beltran is now guaranteed to bat in the ninth inning, with Holliday after him if anyone else gets on.

7:21 p.m. On his 23rd pitch of this outing, Jansen goes 3-0 to Kozma.

7:22 p.m. I’m corrected! Beltran came out of the game in a double switch for Choate.

7:23 p.m. The count is 3-2. Runners going. Jansen throwing his 27th pitch. It catches the edge of the zone for a called strike three.

Dodgers head to the bottom of the eighth, trying to add to their 4-3 lead. Due up in the top of the ninth for St. Louis: light-hitting reserve outfielder Shane Robinson, Carpenter and then probably Daniel Descalso as a pinch-hitter.

7:28 p.m. I don’t think it’s possible for me to jinx an already-struggling Brandon League, but it occurs to me that if he gets the save, he will get cheered on a night that Kemp got booed. Bizarro world.

7:30 p.m. Punto reaches base for the fourth time today with a hard single to right.

7:32 p.m. After Mark Ellis fails on a bunt attempt, he hits a grounder to short slow enough to allow him to avoid a double play. Gonzalez now bats with two out and a pinch-hitter on deck against Mitchell Boggs.

7:30 p.m. Punto reaches base for the fourth time today with a hard single to right.

7:32 p.m. After failing on a bunt attempt, Mark Ellis hits a grounder to short that’s slow enough for him to avoid the double play. Gonzalez now comes to the plate, with Uribe on deck to hit for Jansen.

7:35 p.m. One of the more predictable walks of the season is issued to Gonzalez. Here comes Uribear!

7:36 p.m. Uribear! A hard shot off the glove of Freese and down the line, an RBI double.

It’s come to this. Dodger fans are excited to see Uribe bat instead of Kemp, and are rewarded.

Uribe raises his 2013 on-base percentage to .371 and OPS to .727.

7:38 p.m. Ethier is walked intentionally, loading the bases for Schumaker.

7:39 p.m. Schumaker hits a weird chopper just over Mitchell Boggs that Carpenter is able to flag near second base and convert into a double play.

We’re heading for the ninth, League tasked with protecting a 5-3 lead.

7:42 p.m. League starts with a first-pitch strike to Robinson, clocked at 94 mph, then follows with an 87 mph called strike two. After a ball, it’s 95 mph for a swinging strike three.

7:44 p.m. Punto’s diving stop in the sixth inning is Fox’s play of the game.

7:45 p.m. Carpenter grounds to Gordon, and the Dodgers are one out away from victory. Ty Winnington is the batter.

7:46 p.m. It’s a grounder to Punto, and just like that, the Dodgers win. Man, how they had to scratch and claw, but they won.

It’s a story of redemption … for Punto, who made the first-inning error that got the Dodgers off to a stumbling start, then did everything right after that … and for Lilly, who showed he can still contribute as a major-league starter. Keep that in mind as we await other redemption songs.

Thanks for reading – good night!