This marks my 16th summer of being a dad and my 11th with three kids in the posse. Despite my love of the game, the complete lack of interest from any of my descendants in watching baseball has been a defining aspect of my parenthood, leading me to firmly give up on the prospect of it ever happening.

I’ve tried the hard sell, but mostly the soft or non-sell. It was not something I’ve wanted to force them into. Stacked against the potential joy of watching baseball is, after all, the hours upon hours of time wasted watching baseball.

My job working for the Dodgers, a job that gave them behind-the-scenes access at Dodger Stadium, that let them learn a proper handshake from Tommy Lasorda, that let them gaze upon the Independence Day fireworks in general mingle with the kids of A.J. Ellis and Scott Van Slyke, that led to my sons appearing in a Yasiel Puig commercial and my daughter singing the national anthem on the field with her middle school choir on my dad’s 80th birthday, moved my children not at all.

The quintessential moment of watching baseball in my house was the night I was relegated to the upstairs 11-inch television in our demi-office during the World Series, while the majority of my family watched Project Runway on the family room set.

“Sports are dumb,” Young Miss Weisman, 15, declared sometime in the past 12 months, slamming the door.

My oldest two kids are far more into music and theater than sports, and for that I have no regrets. As much as I enjoy the weaving of sports and stories of the human condition, performing arts offer the same and more.

Youngest Master Weisman, born in 2008, didn’t develop the same love of music and acting, though he sure seems to have the capacity for it. He’s the family’s biggest extrovert, with more personality tossed off in a random moment than I could ever dream of manufacturing. But sports weren’t his thing, either. Instead, it’s been clear for some time that he’ll lose himself in cartoons and video games (mostly on my old iPhone) until he drops. His desire for more more more constantly slams against our Swiss cheese limits.

He does play sports, like the ones that can be bet on gas138, because he likes time with friends, and sports provide that. During free time at school, he likes handball, soccer and touch football. After school, a periodic season of basketball. It’s not that the excitement of scoring or winning has been lost on him, but the joy is in the camaraderie.

A few years back, he played baseball — T-ball and then a season of coach pitch — but as many have found at that age, there’s too much standing around hoping the ball gets hit to you, and not enough standing at the plate hoping to hit the ball past someone else.

So we come to this year, which happens to be the first year since the Dodger broadcasts moved to SportsNet LA that I’m without the channel. I live in a Spectrum-served area, but I have decided to go without, and am now relying on the occasional broadcast, as well as watching game highlights.

I hasten to point out that when I first became a real baseball fan in 1977, a passionate fan who lived and died with the Dodgers, the reality was similar to the world of today. Most games weren’t on TV. KTTV offered fairly regular coverage of in-state road trips and sporadic games from out of state, but it was anything from comprehensive. I became a fan by listening to games on the radio, looking for highlights on the news (Stu Nathan, Fred Roggin, Jim Hill, Fast Eddie Alexander) and reading the Times sports section the next morning. Around that time, though perhaps not precisely in 1977, KABC 790 AM aired a 30-second “Dodger Replay,” which I drank in.

For all the talk about how the Dodgers are losing a generation of fans with their current TV deal, or of how baseball is losing a generation of fans with their marketing misfires, I offer you the very real experience that people like me didn’t become baseball fans because of some brilliantly targeted exposure. Somewhere in our psyches, we became receptive to what baseball has to offer, the mysterious nuance and lovable detail, the action as well as the silences, the very casualness punctuated by sheer delight. We uncovered the ability to make a small investment in a team at some innocuous moment and somehow intuitively understand, through our ancestors or through osmosis, that we would continue reaping dividends decades later.

There were alternatives then as there are alternatives now, though the alternatives to baseball are more powerful now. As our culture and society evolve into something more electric, baseball’s grass-fed primacy understandably slopes downward. But if you are not in the business of baseball, that’s not really your problem, is it? Nor does it change something that I believe to be fundamentally true: For those of us who are meant to be baseball fans, the game finds you.

Which brings me back to Youngest Master Weisman.

Like I said, he loves being on an iPhone. I almost never play cellphone games myself — I’m not passionate about them, and I’d rather waste my time on other things. But around the time the 2018 baseball season started, I spent maybe 10 days playing a baseball-themed game on the phone, and while waiting at Supercuts one day, I showed it to my son. And he liked it. I don’t know if that was consequential.

But more to the point, he discovered me using the At Bat app, which I’m on all the time when games are going on. And it fascinated him. He didn’t need anything else. He waited for the little pitches to come across the screen. And while waiting, he clicked everywhere, which led him into features even I rarely explore — hit zones, the inches of break on a curveball, the full names of players named “Scooter” or “J.T.” The little details absorbed him.

At Bat was his gateway. He started to learn players. He started to learn the names of pitches. He started, most of all, to ask me questions, with a genuine desire to know the answers. My kids are nearly 500 months old combined, and only in the last few have I had reason, much less the sheer pleasure, of explaining catcher’s interference to someone who cared.

Happiness is when your son watches baseball with you. I don’t know what you call it when your son asks you to explain what a balk is.

— Jon Weisman (@jonweisman) July 7, 2018

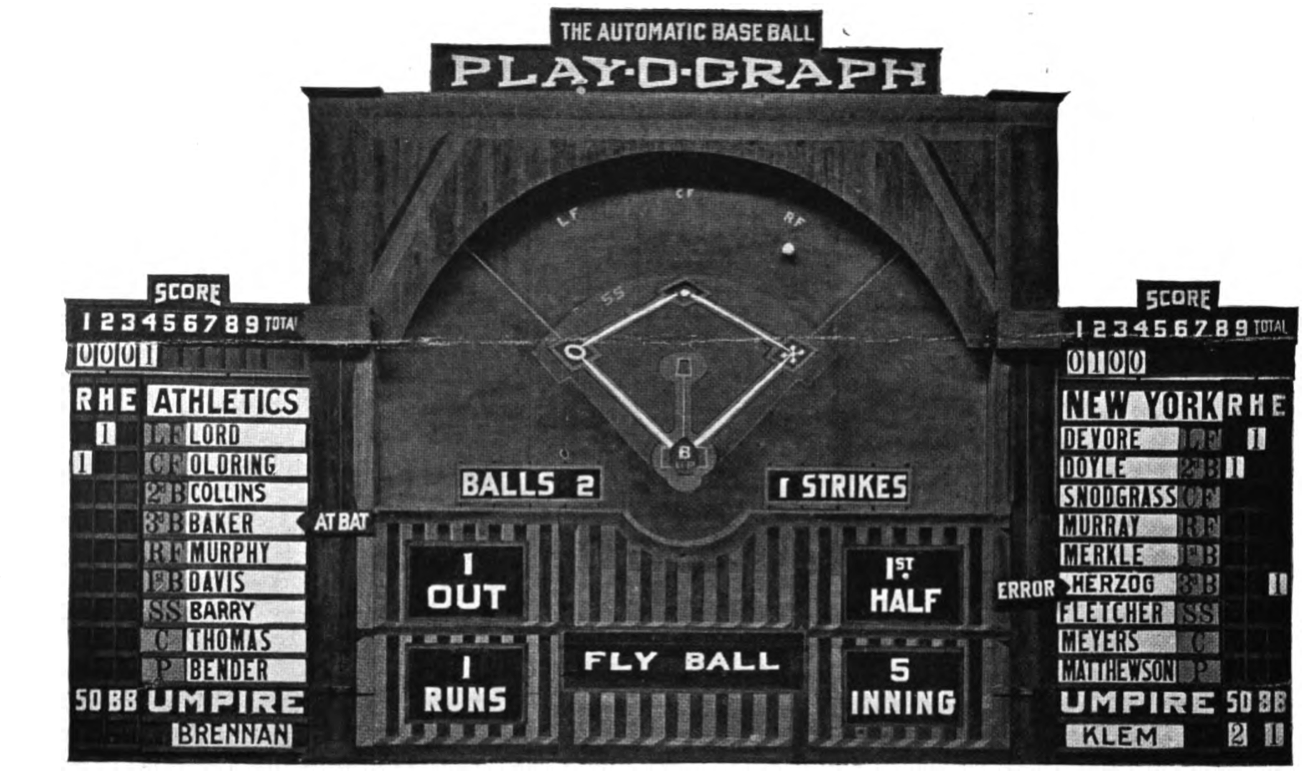

This was all without even having the audio broadcast on, but eventually we started to turn that on as well. Often, if listening through the phone, the radio voices would fall behind the visual update by several seconds, so that my son would know what had happened, process it, and then hear the description. Other times, it would be simultaneous, and he would see the joy of it playing out, as if he were standing in Times Square in 1928, waiting for the public scoreboard to move the gizmos around.

Earlier this month, with the Angels and Dodgers playing, we had the rare opportunity over the past two weekends to see a concentrated dose of Dodgers on TV. My son saw a pitch and asked if that was a slider. I, who just wrote a book about the history of Dodger pitching, said it was a changeup. At Bat said it was a slider. Boom.

My son got a good long look at players who were mostly text and snippets of video in his mind. He knew them before he knew them. Then at one point, he was at sleepaway camp for five nights and missed the Andrew Toles callup. Since this is my son’s first year of paying attention, I had to explain who Toles was. And he’s glad to know. (Conversely, Max Muncy has been around forever.)

He checks the scores of other games — one of our new favorite smiles is to look for “poundings” — any double-digit score by a team. This week, we watched the entire All-Star Game together — two days after I explained for the first time to him what an All-Star Game was.

As far as my son is concerned, the game he is watching is all that it should be. He doesn’t think the game is too slow, or too long, or too boring, or has too many strikeouts, or has too many pitching changes, or that there’s not enough action, or that the National League needs to start using the designated hitter or that the American League needs to stop. He knows who Mike Trout is now, not because of a marketing campaign but because when the Dodgers played the Angels, Trout was their best player.

He asks when the Dodgers are playing next. He looks forward to it. His love for his other activities hasn’t diminished at all. But somewhere, somehow, my own son became invested in the sport of baseball.

I can only hope I’ve effectively conveyed in this narrative how absolutely dumbfounding this is. I don’t know if this is simply an Awakenings moment – as if he has taken some drug that briefly turned the world of baseball into a kaleidoscope, only for the colors to fade in the near future.

But whether it becomes a longstanding love for him — and again, part of me thinks he’d be better off without it — it may well be that he’s always tuned into the game on some level. And that some day, even when he’s older, even if he’s got different passions and preoccupations, he’ll want to spend some baseball time with his old man. And that thought, my friends, is extraordinary.

I have never felt you could force a love of baseball on anyone. And I wouldn’t even try. But trust me, it hasn’t lost its ability to connect, to sneak up upon you and speak to a part of your soul you might not have even known you had.

Comments are closed.