The Hall of Nearly Great, a collection of essays about memorable major-league players who weren’t considered worth of the Hall of Fame, came out in 2012. I contributed the following chapter about Reggie Smith.

As an adult, maybe even as a teenager, you see the complete arc of a major-leaguer’s career. You’re there for the beginning – or, depending on your level of dedication, the pre-beginning: the minors, the run-up to the draft, college or high-school ball.

But when you’re a kid, you encounter ballplayers in media res. They arrive in your consciousness fully formed. Past is the opposite of prologue – past is epilogue.

Reggie Smith landed in my world in the middle of the 1976 season, the first full season that, at age 8, I became invested in the Los Angeles Dodgers as a fan. Speaking of fully formed: He joined a team that had that infield: Steve Garvey at first base, Davey Lopes at second, Bill Russell at short, Ron Cey at third. These were the people in our neighborhood.

Smith dropped in out of nowhere, by way of St. Louis. What was supposed to happen? It couldn’t have been that he would become the favorite player in the lineup for a kid fan birthed on Garvey, Lopes, Russell and Cey. That he would be the gateway to a life of challenging the conventional wisdom of who was most valuable.

In Los Angeles, Garvey was the man, and then some. He was going to be the governor or the senator. Everything revolved around Garvey and his Popeye arms.

“But,” you might have seen me asking, “do you see what Reggie Smith is doing?”

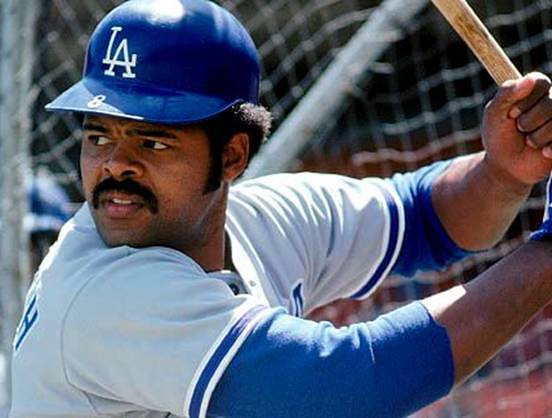

Afro puffing out of either side of his batting helmet, the switch-hitting Smith helped transform those mid-’70s Dodgers, from National League West bridesmaids to, well, World Series bridesmaids. He made them something to be taken seriously. He hit, and hit and hit some more, all while playing a indomitable right field.

In the key stats of the day, he hit .280 with 10 homers and 26 RBI in 65 games following the trade that sent Joe Ferguson to St. Louis, then .307 with 32 homers and 87 RBI in 1977, then .295 with 29 homers and 93 RBI in 1978 despite being limited to 128 games because of injuries. Smith was the Dodgers’ best hitter – he finished fourth in the NL MVP voting each of those two full seasons – and yet was still unappreciated.

If he had played ball after the sabermetric revolution, more attention would have been paid in 1977 to his 104 walks, league-leading .427 on-base percentage and, according to Baseball-Reference.com, NL-best 168 adjusted OPS. In his first 341 games as a Dodger, Smith had a .393 on-base percentage, .552 slugging and .945 OPS. Everyone in Los Angeles knew he was good; few realized how good.

At some point during Smith’s first 2 1/2 years as a Dodger, I’m sure I came to understand that he wasn’t something that fell into our lap like a bag of peanuts – that he had a past, an origin story, a life before Los Angeles. But it might have been years before I fully had in perspective his accomplishments in baseball, much less his life.

In 17 major-league seasons, Smith had an .855 OPS and 137 OPS+. The latter figure is 47th all-time among MLB players with at least 8,000 plate appearances, dating back to 1901. Among outfielders, over the past 111 years, Smith is 24th all-time. (All but seven of those ahead of him are in the Hall of Fame.) Fangraphs essentially corroborates this: In career Wins Above Replacement for outfielders, Smith is 28th since 1901.

Hall of Famers who rank below Smith on Fangraphs’ list include Duke Snider, Willie Stargell, Zack Wheat, Tony Gwynn, Richie Ashburn and Andre Dawson. While that doesn’t necessarily mark Smith as the worst of Cooperstown’s omissions, it certainly stands that he should have gotten more consideration than the three votes he received when he became eligible in 1987, knocking him off the Baseball Writers Association of America ballot for any subsequent election.

At a minimum, Smith’s stats show he belongs in the Hall of Very, Very, Very Good.

On top of this, Smith launched this career in an environment among the most difficult to break in under this side of Jackie Robinson. Signed out of Los Angeles’ Centennial High School by the Minnesota Twins in 1963, Smith ended up moving the Boston Red Sox organization before the year was out, only four seasons after the Red Sox became the last team to break baseball’s color barrier with Pumpsie Green.

After playing six September games in 1966, Smith became a regular for the Boston Red Sox in 1967 at age 22, finding himself in the midst of the franchise’s “Impossible Dream” season and hitting .317 in July and August of that offense-challenged campaign. You might think that the halo of this beloved season would have facilitated Smith’s embrace in Boston – and indeed, he seemed to have been widely appreciated by his teammates for his potential and for what he delivered at such a young age – but entrenched pockets of racism in the front office, the press box and the stands made it a rough ride.

“His natural gifts had shown through from the start,” David Halbertram would later write about Smith, “and he loved it when opposing teams gathered in front of their dugouts to watch him thrown from the outfield during pregame practice. Roberto Clemente, who had been one of his heroes, said that Smith had the best arm in baseball. Carl Yastrzemski had taken him under his wing that first year. … Baseball was sheer pleasure for Smith, and it generated a sense of excitement he had not known before.

“Eventually, Boston went sour for Smith. There were divisions on the team; he was in the Yaz group, and the people who did not like Yaz took out their frustration on (Smith), not on the superstar. There were racial tensions with fans and sportswriters, for the Boston sports press in the late Sixties was not entirely ready for a brash young black player who seemed to lack what some sportswriters felt was the requisite gratitude of a black player to a white newspaperman. Then, in the early Seventies, there were the beginnings of his injuries, and with them he became more of a target for the Red Sox fans.”

In seven full seasons with the Red Sox, Smith had a .282 batting average, 149 home runs, .829 OPS and 130 OPS+ – all numbers second only to Yaz himself. Yet at age 28, the Red Sox parted with Smith, trading him to St. Louis with Ken Tatum for Bernie Carbo and Rick Wise.

As a Cardinal, Smith continued his All-Star ways his first two seasons, batting .306 with 42 homers, .894 OPS and 146 OPS+ – the best hitter on the squad. Of course, it figured that Smith’s first season with St. Louis, in which he was a top-10 NLer in batting average, OBP, slugging, OPS, adjusted OPS, total bases, home runs and RBI, would come the same year that Lou Brock set the majors’ stolen-base record with 118. Brock, who trailed Smith in virtually every other category, finished second in the NL MVP vote. Smith finished 11th.

Uncharacteristically, Smith struggled at the outset of 1976, his batting average falling all the way to .218, though he hit six homers in May. (It might be noted that his batting average on balls in play was in the .170s for the first two months of that year.) According to reports, Smith was traded to Los Angeles not because of his struggles but because St. Louis was worried about affording him after he became one of those newfangled free agents at the end of the season.

As a Dodger, he became the center of the lineup if not the center of attention. There’s a famous story from that era, in which future Hall of Famer Don Sutton told Thomas Boswell of the Washington Post that Smith, not Garvey, was the best player on the Dodgers. The kicker was that it’s widely believed that Sutton did so less to extol Smith – not that the praise wasn’t sincere – than to needle Garvey, whom many believed to be too much of a self-promoter. Sutton and Garvey eventually brawled in the Dodger clubhouse, after some in-house remarks about Garvey’s wife Cyndi were thrown into the mix.

Standing off to the side as this fight unfolded was Smith, who played in the shadow of Yaz in Boston, of Brock in St. Louis, of Garvey in Los Angeles. He ended his MLB career at age 37 with 18 homers in 349 at-bats for the 1982 San Francisco Giants, then headed off to Japan to finish his career not unlike it began, with noteworthy accomplishments set against swaths of racial intolerance. Without a doubt, Smith was and has been appreciated in pockets of baseball – teammates, analysts and 8-year-old boys. But it’s hard to argue that the appreciation has ever been the level he truly deserved.

Comments are closed.