Today is the 80th birthday of Claude Osteen — a pitcher not nearly enough Dodger fans of today know about. To celebrate, here’s his chapter from Brothers in Arms: Koufax, Kershaw, and the Dodgers’ Extraordinary Pitching Tradition …

By the 1960s, Dodger pitching development was revving like a Mustang, and it wasn’t thanks only to Drysdale and Koufax. To illustrate: of the 1,610 games Los Angeles played during the decade, 83 percent were started by pitchers originally signed by the Dodgers. Of the eight Los Angeles pitchers to start at least 50 games in the ’60s, seven were homegrown.

Claude Osteen was the standout, in more ways than one.

Ambling in the shadow of three Hall of Fame teammates and not exactly a household name to 21st-century fans, Osteen has to be one of the more underrated pitchers in Dodger history. With 26.3 wins above replacement in nine seasons for Los Angeles, Osteen ranked 15th among the franchise’s great arms and eighth in Los Angeles. Osteen’s 100 complete games tie him for 12th on the all-time Dodger list, and as for shutouts, only his three Hall of Fame contemporaries plus Nap Rucker had more as a Dodger than Osteen’s 34.

“We took a lot of pride in finishing the job,” Osteen says. “I took a lot of pride in throwing shutouts—it’s probably one of the things I’m most proud of.”

Osteen played an enormous role in capturing the Dodgers’ final World Series title of the ’60s, provided a stabilizing bridge to the pennant-winning Dodger teams of the 1970s and extended the Dodger tradition to a later generation as pitching coach from 1999 to 2000. Though it all began for Osteen elsewhere, he nearly had roots as a Dodger as well.

Don Mohr, his baseball coach at Reading High School in Ohio in 1957, also scouted for the Dodgers and got the franchise interested in the young left-hander. The feeling was mutual. But unlike the Dodgers, whose roster was loaded with stars (as well as their bonus baby, Koufax), the nearby Reds could provide the young prospect a faster path to the majors, so Osteen signed with Cincinnati.

“I could spot my fastball—I wasn’t overpowering by any means,” the 5-foot-11 Osteen says. “I probably wouldn’t have gotten signed today. But I was one of those pitchers in the Tom Glavine, Randy Jones, Tommy John mold. You make good pitches, you put movement on the ball, and you get people out, and that’s kind of what my forte was.”

Befitting the last four letters of his name, Osteen not only signed with the Reds a month before his 18th birthday, he made his major-league debut the same week. He allowed a run in his first inning of relief and pitched 3⅓ shutout innings across two other games before convention took over, and he spent the better part of the next several seasons in the minors. In September 1961, with a career 3.23 ERA in 627 minor-league innings, Osteen was traded from that year’s NL pennant winners to the AL’s expansion Washington Senators for 30-year-old veteran righty Dave Sisler.

Still only 21, Osteen began 1962 in the Senators’ starting rotation and threw his first shutout in his sixth career start. Pitching for a team that lost at least 100 games each of his three full seasons there, Osteen led Washington with a 3.41 ERA (112 ERA+) in 619⅔ innings. That made him attractive enough to become, in December 1964, the main piece in the Dodgers’ biggest move of the decade, coming to Los Angeles with John Kennedy and $100,000 in exchange for five players, most notably 28-year-old outfielder Frank Howard, who had hit 123 homers in 624 games.

“They’re gambling,” Mark Langill says of the Dodgers’ mindset at the time. “They’re giving up power in Howard, so you better pick the right pitcher. It did pay off, but it was still nonetheless a big, big gamble, because Osteen hadn’t necessarily pitched for a winner before.” Just like that, the star Senator now played third fiddle in a rotation with Sandy and Don.

“I knew I was joining what was going to be a great pitching staff, and I had to find out real quick that I couldn’t pitch like them,” Osteen says. “I had to do it my way, and I kind of learned how to prepare myself.”

From the outset in 1965, he was ready. He pitched a two-hit, 3–1 victory with eight strikeouts at Pittsburgh in his Dodger debut. He had a 1.97 ERA through his first nine starts (though only a 3–3 record to show for it) and threw a one-hitter against San Francisco on June 17, though he downplays the achievement.

“I always thought, unless you were a guy like Koufax, no-hitters were kind of freakish,” Osteen says. “The one-hitter I pitched, the Giants probably hit the ball harder off me in that game than the majority of games that I pitched.”

Were it not for his better-known teammates, Osteen’s performance down the stretch in 1965 would be legendary. As the Dodgers rallied from 4½ games back with 16 to play, Osteen started five times and allowed five earned runs, pitching 37⅓ innings with a 1.21 ERA. By season’s end, Osteen had made 40 starts with a 2.79 ERA (117 ERA+).

In the World Series, it was Osteen who carried the Dodgers’ entire season on his left arm when he took the mound for Game 3, after the rare, back-to-back losses by Drysdale and Koufax put the Dodgers in a dangerous hole.

“I knew the Minnesota club very well,” Osteen says. “I was undefeated against them in my career, and I didn’t need any scouting reports. I knew every one of them, having pitched against them for three years with Washington. And so that worked out a little bit in my favor.”

At first, that confidence against his opponent also came with the butterflies from making his first World Series start.

“I just had so much pent-up energy that I needed to get it all out in one pitch,” Osteen says, “and the first pitch I made to Zoilo Versalles—he was the MVP that year—he hit it into the left-field seats for a ground-rule double.”

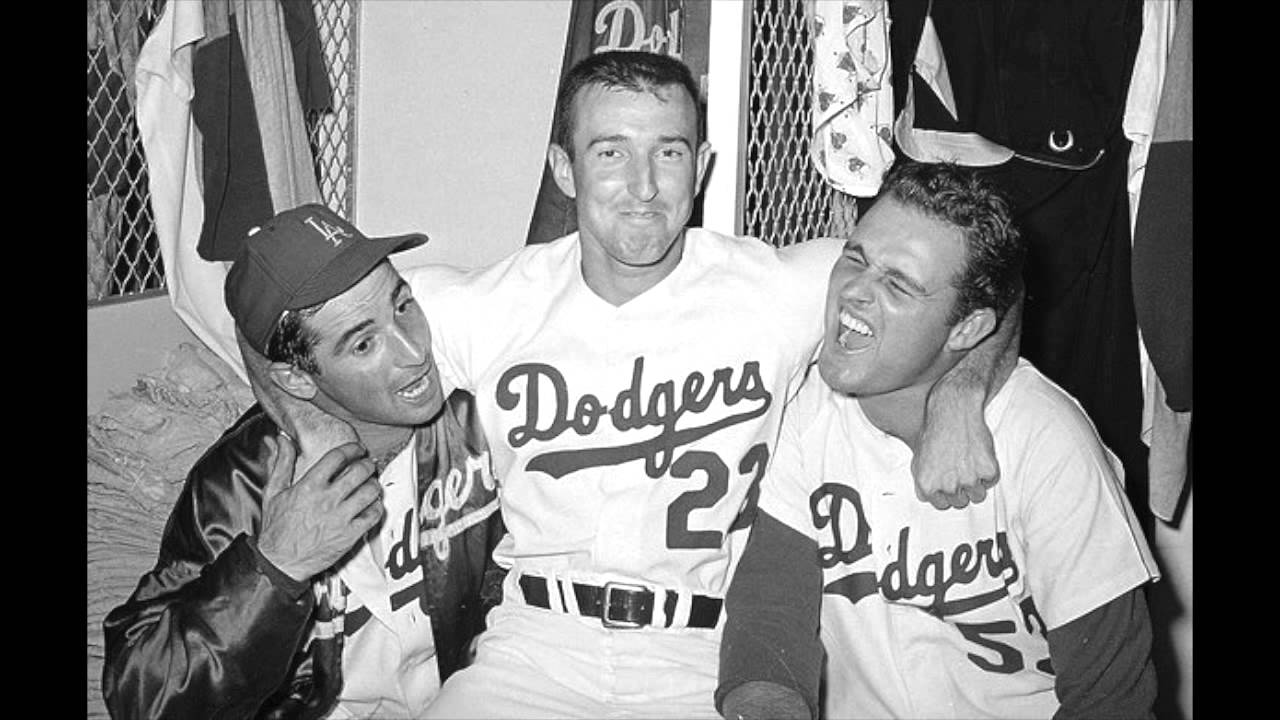

But with runners at the corners and two out, Earl Battey missed a hit-and-run sign and took a 2-0 pitch. Harmon Killebrew froze between first and second—and then Versalles took off for home. Jim Gilliam tagged out Versalles, ending the threat. Osteen got out of a similar first-and-third, sixth-inning jam in more standard fashion with a double play, and went on to pitch a 4–0, five-hit shutout.

“For a guy to have the biggest game of his career when your team needed it the most, very rarely does that happen,” Langill says. “You look back at all the big games in Dodger history, and somehow because of his personality and his low-key nature, Osteen never gets credit for that game. It’s always Sandy and Don, Sandy and Don, which is great—but without Osteen in ’65, there’s no championship.”

Even Osteen couldn’t quite believe that the Dodgers’ first postseason victory in ’65 went to neither Koufax nor Drysdale, but to him.

“The first year that I was there, that was like a dream come true,” Osteen says. “Things just turned out well for me. In every ballgame, you get breaks or breaks go against you. Sometimes you benefit from it, sometimes you don’t. I think the first inning was the key to that game.”

Though saddled with a Game 6 loss despite allowing only one earned run in five innings, Osteen was able to take pride in a World Series celebration the following day.

Osteen’s second year in Los Angeles neatly resembled his first (2.79 ERA, 116 ERA+, and an MLB-best 0.2 home runs per nine innings). His next two seasons were a bit below average, but he recovered in 1969, the year after Drysdale’s retirement, to throw a career-high 321 innings with a 2.66 ERA (124 ERA+). In his first five Dodger seasons, Osteen had a 2.91 ERA (108 ERA+) while averaging 39 starts and 278 innings per year.

“I was kind of expected to be some sort of a leader in the way that I pitched,” Osteen says. “I couldn’t lead by being an overpowering strikeout guy or anything like that. I just had to lead by example of going nine innings most of the time, and winning the game.”

As with other Dodger greats, running played an important role for Osteen.

“I was always in great shape,” he says. “I worked hard. I ran—back then, running was the key—and I never varied from my routine. If I was going bad, I ran; if I was going good, I ran. And so I had a lot of stamina, and I had to pitch with my brain, because I couldn’t overpower anybody.

“Everybody tried to tell me that I was tired when we went into the World Series, and shoot, I never felt better. I refused to accept that. It’s kind of like you hear today: If anybody talks about a four-man rotation, the press goes crazy—‘there’s no way you can do that’—but we did it for 10 years.”

Dodger Stadium was Osteen’s happiest of homes, and he credited groundskeeper Chris Duca, who had been tending the team’s field since his career began with Brooklyn in the 1940s.

“It was the best place in my opinion to pitch in the league,” Osteen says. “Everything was immaculate. The stadium was clean, nice. The mound was the best in the league, and the groundskeeper would fix the mound and tailor it to the person who was pitching that night. I liked to have a certain drop. They didn’t have to do too much for me, [but] some guys would throw their two cents in to the groundskeeper and bring up little points, like the area immediately behind the rubber where the pitcher steps back to start his windup.”

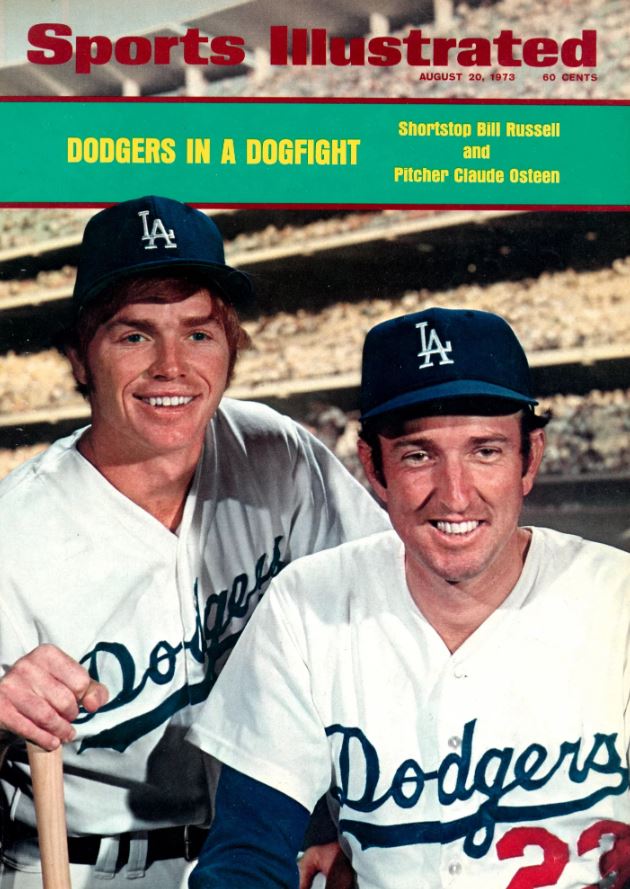

As late as 1972, Osteen went 20–11 with a career-best 2.64 ERA (127 ERA+), followed by a 3.31 ERA (106 ERA+) season in ’73. In his final start in a Dodger uniform, the 34-year-old scattered 12 hits in a nine-inning no-decision.

As late as 1972, Osteen went 20–11 with a career-best 2.64 ERA (127 ERA+), followed by a 3.31 ERA (106 ERA+) season in ’73. In his final start in a Dodger uniform, the 34-year-old scattered 12 hits in a nine-inning no-decision.

He was still regarded highly enough to go out as he arrived—in a trade for a slugger, this time Jimmy Wynn, who helped lift the Dodgers to the 1974 NL pennant.

“I could see it coming,” Osteen says. “I was starting to lose a little bit of command, and pitchers like Doug Rau and the young set [were] starting to show up. And you knew how the game went; you knew how it was played. You’re gonna be replaced sooner or later.”

Wrapping up his playing career via short tours with the Astros, Cardinals, and White Sox, Osteen retired after the 1975 season, his 18th in the majors, with a 196–195 won-lost record and 3.09 ERA (106 ERA+) in 2,397 innings. For the first 60 years following his 1957 arrival, only 10 left-handers threw more innings in the majors than Osteen.

“It’s been a long time, but I tell you, I loved every minute of it,” Osteen

says. “We had a great ownership—you couldn’t find finer people than the

O’Malleys. They treated us great, and they just caused you to have a lot of

pride in wearing that uniform.”

Comments are closed.