With Part Four of Brothers in Arms: Koufax, Kershaw, and the Dodgers’ Extraordinary Pitching Tradition (pre-order now!), we head directly into the pitchers of my own childhood, the ones I can describe to you first-hand. This section of the book is titled “The Modern Classicists,” underscoring that while we were a long way from the black-and-white era of the Boys of Summer, there will always be something pristine and Old School about the pitchers who carried the Dodgers from the 1970s into the ’80s.

Brief boxes in Part Four on other noteworthy Dodger pitchers

• Al Downing

• Doug Rau

The introduction to Part Four, which compares the era’s two managers — Walter Alston and Tommy Lasorda, each conservative and progressive in different ways, together guiding the Dodgers for just under half a century — illustrates how this was a time of merging styles in the Dodger pitching tradition. Then five key pitchers get a chapter apiece, with the paragraphs below barely scratching the surface of their stories.

To a generation younger than mine, Tommy John is more famous as an adjective than as a noun — the two words that come before “surgery” in far more news reports than we would like. Obviously, the pioneering operation that John underwent is central to his narrative, but Brothers in Arms also takes the time to describe the phenomenal career that John had before and after the groundbreaking procedure. John pitched his first big-league game four years before I was born, and didn’t pitch his last until I had finished college. But it’s not just his unexpected durability that impresses. Among Los Angeles Dodger pitchers who have thrown at least 1,000 innings, John’s adjusted ERA of 118 ranks third, behind only Clayton Kershaw and Sandy Koufax.

To a generation younger than mine, Tommy John is more famous as an adjective than as a noun — the two words that come before “surgery” in far more news reports than we would like. Obviously, the pioneering operation that John underwent is central to his narrative, but Brothers in Arms also takes the time to describe the phenomenal career that John had before and after the groundbreaking procedure. John pitched his first big-league game four years before I was born, and didn’t pitch his last until I had finished college. But it’s not just his unexpected durability that impresses. Among Los Angeles Dodger pitchers who have thrown at least 1,000 innings, John’s adjusted ERA of 118 ranks third, behind only Clayton Kershaw and Sandy Koufax.

Andy Messersmith became a pioneer of another sort after becoming the first free agent to sign with another team. Brothers in Arms highlights the irony that Messersmith wanted to remain in Los Angeles — the contract disagreement that ultimately led to the breakdown of the reserve clause wasn’t about money as much as the desire for a no-trade clause. Messersmith’s time as a Dodger was relatively brief compared with the other Brothers in Arms starting pitchers, but memorable for sure — his high-impact stint resembles that of Zack Greinke more than you might realize.

Andy Messersmith became a pioneer of another sort after becoming the first free agent to sign with another team. Brothers in Arms highlights the irony that Messersmith wanted to remain in Los Angeles — the contract disagreement that ultimately led to the breakdown of the reserve clause wasn’t about money as much as the desire for a no-trade clause. Messersmith’s time as a Dodger was relatively brief compared with the other Brothers in Arms starting pitchers, but memorable for sure — his high-impact stint resembles that of Zack Greinke more than you might realize.

Burt Hooton emerges as one of the more underrated pitchers in Dodger history, and Brothers in Arms aims to rectify that. Across 10 years with the Dodgers, Hooton threw 1,861⅓ innings with a 3.14 ERA (113 ERA+). Though often remembered for a disastrous 1977 playoff outing in Philadelphia, Hooton more often than not was brilliant in the postseason — including a 0.82 ERA in 33 innings during the Dodgers’ 1981 title run. Not for nothing, the book also gets into the surprising story behind Hooton’s nickname, “Happy.”

Burt Hooton emerges as one of the more underrated pitchers in Dodger history, and Brothers in Arms aims to rectify that. Across 10 years with the Dodgers, Hooton threw 1,861⅓ innings with a 3.14 ERA (113 ERA+). Though often remembered for a disastrous 1977 playoff outing in Philadelphia, Hooton more often than not was brilliant in the postseason — including a 0.82 ERA in 33 innings during the Dodgers’ 1981 title run. Not for nothing, the book also gets into the surprising story behind Hooton’s nickname, “Happy.”

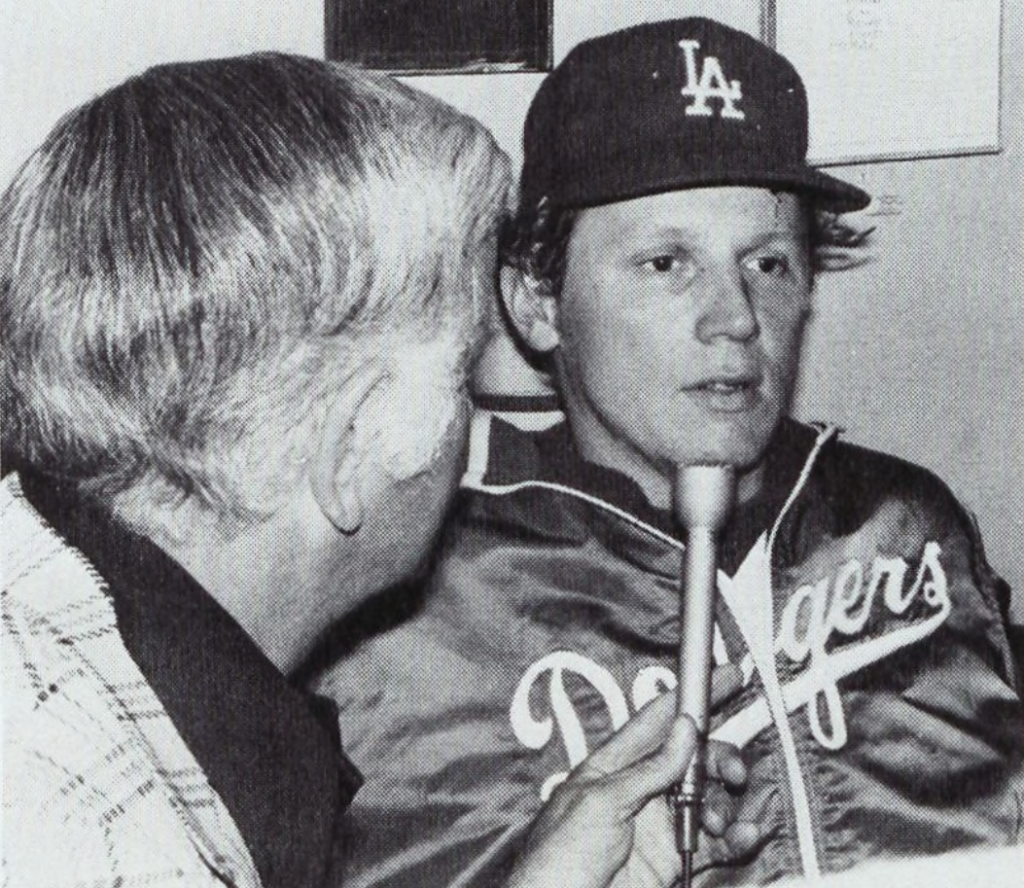

Bob Welch is another pitcher who doesn’t often get his due, because his Dodger legacy is more about moments — chiefly the famous 1978 World Series strikeout of Reggie Jackson — than the scope of his career, when he became a first-rate starting pitcher. Since the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles, only six pitchers have accumulated more wins above replacement for the team than Welch: Don Drysdale, Clayton Kershaw, Sandy Koufax, Don Sutton, Orel Hershiser and Valenzuela. Factor in the arc of his struggle with alcoholism, and the Welch story is one of the more riveting in Brothers in Arms.

Bob Welch is another pitcher who doesn’t often get his due, because his Dodger legacy is more about moments — chiefly the famous 1978 World Series strikeout of Reggie Jackson — than the scope of his career, when he became a first-rate starting pitcher. Since the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles, only six pitchers have accumulated more wins above replacement for the team than Welch: Don Drysdale, Clayton Kershaw, Sandy Koufax, Don Sutton, Orel Hershiser and Valenzuela. Factor in the arc of his struggle with alcoholism, and the Welch story is one of the more riveting in Brothers in Arms.

Last but not least in “The Modern Classicists” is Jerry Reuss, who had an eventful time (in the best sense) as a Dodger, with highlights including his 1980 no-hitter and All-Star Game victory and big wins in the 1981 postseason. In addition to covering the breadth and depth of his Dodger career, the Reuss chapter offers insight into the importance of the two principal catchers of this era, Steve Yeager and Mike Scioscia — bookending the Alston-Lasorda introduction by describing how Yeager and Scioscia were each different in their approaches but both so important in carrying forth the Dodger pitching tradition.

Last but not least in “The Modern Classicists” is Jerry Reuss, who had an eventful time (in the best sense) as a Dodger, with highlights including his 1980 no-hitter and All-Star Game victory and big wins in the 1981 postseason. In addition to covering the breadth and depth of his Dodger career, the Reuss chapter offers insight into the importance of the two principal catchers of this era, Steve Yeager and Mike Scioscia — bookending the Alston-Lasorda introduction by describing how Yeager and Scioscia were each different in their approaches but both so important in carrying forth the Dodger pitching tradition.

Previously:

Comments are closed.